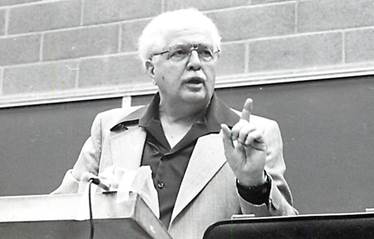

DOES GOVERNMENT PROTECTION PROTECT?

By Robert

LeFevre

Thank

you very much, Ken, and ladies and gentlemen. If you can spare a copy

of that, Ken, I'd like it because I'd like to look up some of the words and find out what you

said.

Actually, I

understood what you said, but I will do two things. One, I'm going to deny the story about the fly. That's not

true. But the story about the sheriff is true and I don't mind telling

you about it.

It

was when we had the campus in Colorado and the plot of land that we had was

sandwiched between two other privately-owned plots. The people behind us had

no means of access to their property except by means of a road that went

through our property and for which they had an easement. After a very

severe winter, more or less normal for some of the high mountains in Colorado,

the runoff precipitated floods which washed away the bridge spanning

the stream over which the access road went. Thus our neighbors behind us

had no means of getting in or out of their property. I noted that fact and presumed

they would do something about it. It was their task to keep the road in

repair, mine to let them go back and forth. Well, my son notified me one day that

there was some heavy equipment that had been moved in, and I figured it would be used to

replace the bridge.

And

he said, "No, Dad, they are tearing into the bank on our side of the property

line."

I

hastened to look, and my son was correct. Our neighbors were, in fact, encroaching

on our land not merely by parking on it, but they were engaged with steam shovel and bulldozer in putting in an

entirely new road on our land. I was

emotionally upset. And I paced the room trying to figure out what in the world I could do. I didn't want to get a gun, not

because I wouldn't hurt a fly, but I simply didn't think that was the

way to handle these things.

What

could I do? Well, I finally succumbed. You're right and whoever reported

it was correct. I called the sheriff. The minute I dialed the number, my secretary said,

"Who are you calling?"

And I said,

"I'm calling the sheriff."

And she said,

"What?"

The

tone of her voice and the look on her face shocked me so that when he came

on the line all I was intending to say to him vanished from my mind. Instead,

I said, "Do you have the phone number of the people who live behind us? I'd like to

telephone them."

He

said, "Sure," and gave me the number. That's all I got from the

sheriff.

Here's

the rest of it. I called my neighbor, introduced myself on the phone and

said, "Do you understand what you're doing? You're back there on my land,

tearing out some of my property and you didn't even ask for permission."

There

was a silence at the other end of the line and then: "Oh, my God, Oh my,

Oh, Oh, ah yes, yes. Yes, of course, you're right." He said, "Oh,

Mister LeFevre, you're new in this area. Where I've put the road

now is where it once was. But that was before you moved in and

you would have no way of knowing that. I'm terribly sorry. Believe me, I'll

go right back and I'll put everything back the way it was. We've taken out a few

trees. I'll replace them. I'll put it

all back the way it was. I wouldn't have done this

for the world." He was practically groveling and I began feeling better

and better.

Finally,

my reasoning powers took over. One of these days I'd like to buy his property

and the place where he was putting the road was exactly where I'd put it if I

owned the property. He was probably saving me expenses later on.

So instead of hanging up, I got over my hang-up and I said, "Mister Blank,

now that you've been so nice and apologized I think

we'll just call it a draw. Why don't you just go ahead doing what you're

doing." It turned out to be a vast improvement. So there it is. You see

how much need we really do have for the government in situations such as this.

Anyway,

Ken's introduction got right to the point as he so frequently does. I've talked

to many people over many years and one of the big questions that is

raised is how much government do we really need. Of course, a great many,

I suppose fundamentally the conservative—those who think of themselves as the

rock- ribbed property-owning productive people—will say to me,

"Well, there's just one thing for the government to do and that is protect

our lives and property." Now, if I go outside the Orange County area, or

any other area dominated by conservative thinking, I will

find extensions to what the government has to do... "Of course,

the government has to protect our lives and property but, in addition, put in

the roads. After that, we're all right." Or "The government has to

protect our lives and property and put in the roads and schools and provide us

with tariff protection from trade with those other people who aren't as we are

because they work for less money than we do, and therefore, we have to have

the government protect us from them." And so it goes. The further away you

get from Orange County, the more things you find government has to do.

Well,

I deny I'm as pure as Ken says I am, but I try to take a position based on reason. And I

try to be a realist about it.

A

NUMBER ONE SUCCESS STORY

My

question for tonight is: Does government protection protect? I think that is really the

point.

We're

right in the middle of this big debate over Proposition 13 versus Proposition

8. I'm sorry that, at the moment, I'm not getting the kind of reaction I would like to hear from either side in

the debate. Because while the proponents

of Proposition 13 say they're going to win, the proponents of Proposition 8 say they're going to get even. If

you vote for 13, they're going to reduce

the size of schools or cut them out. And they're going to reduce police protection and fire protection. And, of course,

the reaction I hear from the populace

is "Oh, you can't do that. We've got to have those things." Now, if

we were really for Proposition 13,

what we would do when we heard these opponents

say "if you take away our power to tax your property, we're going to close the schools" would be to laugh and

say, "Swell, they deserve to be closed.

We're going to set up our own." When they say, "We're going to reduce

your fire protection," we ought to say, "Gee, that's marvelous; it's going to give us some great opportunities to make

some money." And we'll call up

the fire department at Scottsdale, Arizona, which is doing nothing but make money, and model our system along those

lines. It's a private system. It has

been operating for about thirty years. It's a number one success story.

And then when the opponents say we're going to reduce

police protection, we'll talk about private protection. We're going to take a look

at that tonight. So let me move directly to that area.

LAWS OF REGULATION—NOT PROTECTION

Ladies and gentlemen, the desire for protection is

probably the most deeply embedded conviction respecting government

that most people have. Maybe more. It is a belief that you and I are helpless

in matters relating to our own protection. And so we have to let government

handle the problem. Now, were we to conduct any study on the subject, we

would first of all discover that governments from time immemorial have never

really said they were going to protect us. If you examine, for example, the

Code of Hammurabi, which was drafted about 1750 B.C., you'll find this ancient

Babylonian lawmaker suggesting what has since become categorized

as lex talionis, the laws of retaliation, not the laws of protection.

So the very first thing for us to do tonight is provide a

definition for certain terms so we can be in communication. We have,

in fact, become confused because of our dependence on government in this area.

We've taken four or five ideas and lumped them together and

called them protection. Let me identify the ideas. One: we think of

retaliation as a part of protection. Two: we think of punishment as a part of

protection. Three: we think of restitution as a part of protection. Four: we

think of defense as a part of protection. And five: we think of

protection as protection. We think of protection as including all

five concepts. If we are going to understand our subject, we will have to analyze each

concept clearly and carefully.

I'm going to use the word protection to mean just one

thing. I'm going to define the word and I'm deriving the meaning

from the roots of the word itself to mean that when you are protected, in fact,

you are safe. Nothing happens to you. Never mind whether anybody wants to

hurt you or not; if you are protected, you aren't hurt.

In your mind, think of the word protection as meaning

safety. I'm going to submit, ladies and gentlemen, that safety is

really what you and I want. We would like to be safe in our persons and

property. We don't want to be injured. We are sensitive creatures. We experience

pain if someone thrusts a knife into us, shoots a bullet into us, or even

swats us. We don't like those things to happen. So we want to be protected because we

want safety. I think we should be protected.

The word retaliation does not mean protection.

Retaliation, in fact, is as far removed from protection as competition is

removed from monopoly. If you have to retaliate or if you believe you do,

it proves that you weren't protected. These are mutually exclusive terms. You

cannot have them both at the same time. You either are protected or you aren't.

If you aren't, then you may have been hurt. After your injury, then maybe you

could retaliate. But there is no way you can retaliate if you haven't first

been hurt. And if you didn't get hurt, then you can't retaliate. Is anyone having problems with that?

Okay, fine.

Now

what is punishment? Punishment is something inflicted on someone by

an authority over him like his mother, his father, or Big Daddy State or whatever.

Of course, we have masochists who inflict pain on themselves, claiming

they enjoy it. So pain is not really punishment from their point of view. The

word punishment itself means the infliction of unwanted injury, harm, pain,

something unwelcome upon someone by someone else who has somehow

managed to get into an authoritative position. This is not protection.

Now

restitution. Restitution means that something taken away from you is restored. That

isn't protection, either.

And

defense. Defense is what happens in the heat of combat when somebody hits you

and you hit him back hoping to curtail further blows. Defense means

an actual combative situation with both sides engaged in essentially the

same thing. Defense isn't the same as protection. It is the first step toward retaliation when

protection is inadequate. The Arabs have a proverb that "All wars begin with the second blow." Clausewitz says,

"Every act of war is an act of

retaliation." I hope to stay away from defense as much as I can although I don't mind getting into it. Because,

after all, if we're going to talk about protection, we may have to open

it up.

Now,

ladies and gentlemen, I submit that you do not want to retaliate, that you

really don't want to punish anybody, that you don't even want to defend

yourself, and you don't want to receive restitution because you'd prefer to be

in a position where nobody has to make restitution to you. That all of those things

are undesirable in terms of what you really want. What you really want

is protection. And if you have protection, in fact, the rest of this becomes academic.

If you're protected, in fact, we can put the questions of defense, restitution,

punishment and retaliation aside.

It

all comes down to protection. The question is: Does government protection

protect? Through long dependence on the government, we have become guilty

of lump-think. We lump all these concepts together and we call it all protection.

BASE

FOR COMPARISON

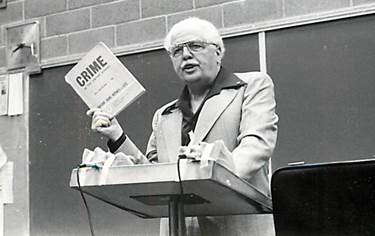

Now

I'm going to show you just how well the government

protects you. (Holds up several

books.) I have been making a collection of these little goodies for a number of years. These are the

United States Federal Bureau of Investigation

Uniform Crime Reports that are issued every year. And I have a shelf full of them. I have them going clear

back into the 1940's. I have gotten one

every year for all that time. Now, I brought with me tonight just a few because

I didn't want to be excessively burdened.

Now

I'm going to show you just how well the government

protects you. (Holds up several

books.) I have been making a collection of these little goodies for a number of years. These are the

United States Federal Bureau of Investigation

Uniform Crime Reports that are issued every year. And I have a shelf full of them. I have them going clear

back into the 1940's. I have gotten one

every year for all that time. Now, I brought with me tonight just a few because

I didn't want to be excessively burdened.

I

have the 1970 Uniform Crime Report, 1971, 1972, 1975, and 1976. And I'm going to show you what the FBI says their record is in handing crime or in

protecting you from the bad guys. Okay, the so-called bad guys.

I still use the 1970 Report for a number of reasons.

One of these is the last report that the FBI has put out that

has within it a ten-year composite study. I'm hopeful that in 1980, they will

come up with another ten-year report. I think the room is small enough so I

can hold this up and if you have good eyes, you ought to detect the direction of these curves.

Now,

that is a ten-year study of how the government has been fighting crime.

From 1960 to 1970, in that period of time, crime in all categories in the United

States went up 176 percent. The rate went up 144 percent as opposed to a

population increase of 13 percent. Now, ladies and gentlemen, that means that according to

the FBI figures, crime in all categories in that ten-year period went up better

than ten times faster than the population.

Inside, if you care

to read these dreary things, you will discover that actually the increase of crime at the particular time,

instead of taking place in the areas where the population was expanding, was

taking place in the suburbs basically and not in the so-called ghetto areas.

Now, it fluctuates back

and forth, but at this time, it was taking place in the suburban areas. So that

clearly the rate of increase of population has no necessary connection to the crime rate. What is shown over

many years is that population density and population growth had no necessary connection with the

incidence of crime or crime growth. Population

growth and the growth of crime fluctuate. Nothing

that I know of can tie them together in any kind of cause and effect relationship.

So that's the statistical story of crime, in general.

Now,

crimes of violence over the same ten-year period—up 156 percent. Crimes against

property for the same ten-year period—up 180 percent. That's the ten-year

study. I'm going to refer back to that book later on.

Just

to be sure that the impact of what the FBI says reaches you, let me sum it up

this way. First, let me make an explanation. Nobody, including the FBI, says these figures

are accurate. They are bound not to be accurate for the reason that all we have here are the crimes that have been reported.

Obviously, many crimes are not

reported. Additionally, there is bound to be some increase in crime every year as long as the

legislators stay in session. There is bound to be, because every time a new

piece of legislation is enacted, somebody

is bound to trip over it. And, of course, when you trip over it, you've violated a law. And that's going to classify you

as a lawbreaker, hence a criminal.

You might be a minor criminal but that depends on how badly the legislature

wanted that particular piece of legislation. The fact remains that nobody

says that these figures are accurate. There is one merit that these reports have and it makes them the best

information that we have that comes out regularly in the country. Or at

least it did until currently. They are uniform. These are uniform crime

reports. Consequently, whatever errors are

made are made consistently. So we have a base for comparison if nothing else.

PYRAMIDS AND THE

WRONG DESTINATION

To

be sure that the impact of my point is not lost, let me offer an analogy. I so

often find that when I'm trying to make a point

with some of my students that if I hammer away at a given idea, I

sometimes hammer their minds closed. I

don't mean to do that. Sometimes when I approach something from an angle

it is easier to see.

Let

us suppose that all of us here in this room work for a moving and transfer

company. Let us suppose also that we are good. In fact, we are so proud

of our work we have emblazoned on the sides of our trucks a motto which

reads "WE CAN MOVE ANYTHING MADE BY THE HAND OF MAN."

And we do a lot of business. One day we are approached by a potential client

from Egypt and he says, "Is that true? Can you really move anything made by the hand of

Man?"

And we say,

"We think we can. What do you have for us?"

And

he says, "Well, we have an idea in Egypt that were we to move the Great

Pyramid of Giza from its present location to a few miles north of Cairo, it

would be a better tourist attraction. Money's no object. We've got money. So we'd

like to move the pyramid. Now you understand, it has to be moved intact

because, you know, that thing wasn't put together with cement. Those blocks are loose. They just fit. We don't want any

vibration. Can you move it as one

piece without damaging it and set it up 25 miles north of Cairo?" The entire distance, we'll imagine, for purposes of

this illustration, to be one hundred miles. "Can you move it?"

Of

course, we start to laugh about this time and say, "Well, of course, we can move it but you

realize that this is going to cost you."

And

our client says, "Money is no object. We really would like to get it moved. Can you give

us a fixed bid?"

And

we say, "Well, sure, we can do that. We'll send a team of experts over and

get you a quotation." So we get our best team and we send them to Egypt. And

they spend six months over there measuring, calculating, and doing all of

the things necessary. And then the team comes back and they say, "You're not

going to sell this one. It can be done, but it's a massive job." And they describe

all of the problems. And they say, "The cost is going to be one billion dollars;

that's a thousand millions. That is a great many dollars. So your client's

going to turn you down." And we say we think so, too, but ho ho, we'll try it. We give the

quotation to our client.

And

he says, "It's no problem. Go ahead. Here's your billion dollars." We

design the equipment, go to Egypt, tie onto the pyramid

and tug for a year. Then we get out and measure and discover we

are 125 miles from the destination. Our client asks, "What went

wrong?" And we say. "We underestimated the job. It's going to take

more money than we thought. We need two billion more on top of

the one you gave us. Why don't you drop it?" But our client says, "No, we

want it moved. Here are the two billion. Move it."

And

we say, "Yes, sir." And we hook on and pull for another year and we get

out and measure and we are 175 miles from our destination. And we repeat

the process the third year and find we are 300 miles away from where we

want to go. Would you begin to think you're doing something wrong? Well, that is what we are

doing with protection.

LAWS

OF RETALIATION

Let

me show you, if I can, the system that we have. The system that we have is

based on the Code of Hammurabi which didn't work well even then and is not

working well now. It's lex talionis, the law of retaliation. I'm going to explain a little more about it, but I want you to get the picture.

Here's the way we do it.

The

first act in this little drama is this. You and I are afraid that there are some

kooks out there who could hurt us. And I'll tell you something. It's

true. So we're afraid of that. We

feel completely inadequate and the government, of course, has been telling us for years that we're inadequate about everything except earning a living so they can tax us.

We authorize the creation of government and the very first thing the government

does is to perform an act of major

predation. Isn't this nice? And by major, I mean it involves everybody in the territory over which the government

holds sway. It goes out and rips off

everybody so that it can get the money together so that nobody will rip you

off. That's the first act.

After that is

performed, the next act is a private one. I'm going to call it minor predation. Not because the act isn't

serious; it could indeed be murder but

the numbers of persons involved are necessarily few. And, therefore, it is minor as opposed to major in the sense that it involves

all. So this act occurs in spite of what we've

done to forestall or prevent it.

Now after that has

happened, the third act in our little drama — also provided by the government — is an act of minor predation in which the government goes out, tries to find the person

responsible for act two, once in a while

succeeds, brings him in and tries him, hopefully convicts him and then punishes him. That's the system. That's the way we

have it set up. I call the third act

minor because the only people suffering here are either the criminals

themselves or those who were mistakenly in the wrong place at the wrong time and are taken to be criminals and those

closely associated. But it's minor

in the sense it doesn't touch all of us. Another act like act two.

Okay,

and then we go to act four, this one also provided by the government. We

have another act of major predation as the government goes out a second time

and steals from everybody in the area to get the money to pay for the services rendered

in act three. Take a look.

You

and I are worried about act two. We're worried about being privately injured.

As a result of that worry, we authorize this and this and this (acts 1, 3, and

4). And private injury not only happens anyway, it happens with increasing

frequency the more of government we authorize. The government’s own figures

confirm it. Now study that a bit, concentrate on it, and see if you can come

up with a worse system if you tried. You can't win here for losing. This is

a disaster. It's worse than I've let on. Oh, believe me, this is incredible. I'll give you a few further insights just to give you

an idea how successful the police are.

I'm going back to the Uniform Crime Report of 1970.

In 1970, ladies and gentlemen, there

were 2,169,300 burglaries in the United States. That's just burglaries. It has gone up since then. The losses

total $672,000,000. Now, get these

figures. Nineteen percent of the burglaries were solved by the police, 9 percent were convicted, 3 percent served out

their time or are still serving time.

Now,

do you see the implications? That means if you're a burglar, you have an

81 percent chance of doing your burglarizing without being caught, a 91 percent

chance of not being convicted, and a 97 percent chance of not having to

serve out your time. That's better odds than you can get in Vegas if you own the casino.

Admittedly,

burglary is one of the most difficult areas for the police to deal with. I'll explain

why in a moment.

Let

me give you the corresponding figures in the area where, strangely, the government

has been improving fantastically. In fact, I'm going to the area where they

used to be the worst and are now getting better. They've made great strides in

apprehending murderers. Of course, they can't catch the Hillside Strangler and

lots of others.

Their

records indicate there is a 21 percent likelihood of arrest; their rate of conviction and

punishment is about on a par with burglary.

You

can take a relatively comfortable position, put all crime together and say

the police are successful 20 percent of the time, from a low of 19 percent to a

high of 21 percent. Twenty is a comfortable middle which means the police are unsuccessful 80

percent of the time.

Now

I want to make this point clear. I am not engaged in attacking the police.

I think something could be said in that area. It is not my purpose to vilify

the police officer. I have met many of them. You do find a few slant-browed,

long-fanged Neanderthals but the bulk of them are actually very nice fellows.

Mostly, they're pretty honest and they're carrying on a tough job.

So we don't have to be down on them. They simply can't do the job they're hired

to do for reasons which will emerge as we proceed.

Let's

get back to one of the points I was originally making to show the difference between

protection and retaliation.

What

you want is protection. You want to be safe. What the government does

is to try to retaliate after the fact. I know it's comforting to believe that

if somebody rips of your television set the cops will find

it and bring it back. It's comforting to believe that. And once in a while

it happens. The police are usually not there when the theft occurs. There's an old adage that

says the police are never around when you

want them. We laugh about that and conclude

that the police are not very sharp. Don't blame the police. Very few crooks

perform with a police audience. And because the police wear distinctive

clothing and carry noisemakers and have flashing lights, you can see them as

far as you can see. Therefore, there's no point in performing a criminal act when the criminal knows the police

are in the vicinity. So he waits and

the police will leave presently. Then he performs the crime. That is why the police have a great deal of difficulty in

catching people after the crime is

committed. Because—and you can ask them—they don't know who did it.

POLICE ARE NOT

MAGICIANS

I've had some

experiences which illustrate the point. One time at the Gazette Telegraph in Colorado Springs, somebody threw a boulder

through two of our big glass doors.

In due course, the police arrived and made all the appropriate

inquiries. There were two policemen with guns. They were ready. We had the rock in the lobby. The officers

took notes and then they looked at me

and said, "If you ever find out who done it, tell us and we'll be glad to

pick him up."

What

did you expect? Police are not magicians. They're good people but they

weren't there when the crime took place. I wasn't there. The only one there

was the crook. This is one of the reasons the police record is not really scintillating.

Despite

the difficulties the police have in acting after the fact, they once in a while

have success: twenty percent, give or take a fraction either way. That's remarkable

in itself. Twenty percent. A very difficult twenty percent. Of course,

we're talking about crimes where restitution could be made. Somebody

steals my TV set; there are other TV sets. I could get one back. Money could be returned,

theoretically, at least. It's possible.

But what about a

really serious crime, an irreversible crime, a crime for which restitution is impossible. Don't tell me

the joys of catching the man who

murders my wife. I don't want the man who murders my wife because I don't want my wife murdered. What do you want me

to do with him? If I have to collect people, I'd like to collect nice people. I

don't want to collect murderers.

I don't want my

wife murdered. I want her to be safe.

Don't

tell me the joys of catching the fellow who rapes my daughter. I don't want

my daughter raped. What do you want me to do with him, rape him? I don't want him.

What

about the man who kidnaps my son? I don't want to catch him. I want my son safe from

being kidnapped. These are the serious crimes. I'm not suggesting that theft is

not serious. But I mean irreversible crimes, crimes where restitution is absolutely impossible. Don't tell me that the

system we have is going to work.

The

system can't work unless it involves protection. What do you want to do, punish somebody

because they have done some terrible thing?

I submit that what

you really want is to stop the terrible things from occurring before they happen. You don't want to be hurt. You want to be

safe. I hope you do. If so, I'm with you.

I can't run as fast

as I used to and I'm getting brittle so I break easily. Really, I want to be

safe.

And

restitution. Nay, I want to be safe to start with. And may I point out, if we

have protection, in fact, retaliation is impossible. Restitution is impossible.

The question of restitution or retribution becomes academic. What we need is protection.

GOVERNMENT

POLICE & TRAINING

The

government never said it was going to protect anyone. Oh, maybe currently some of

the politicians tell you that. But all anyone has to do is examine the facts. Government is a bunch of rules

which say that if you break them,

government will hurt you. It's not going to prevent these rules from being broken. Government is designed only to

retaliate and is successful only 20 percent of the time.

Now,

people, protection is easier than retaliation. You can have a higher

achievement average if you understand what protection is than if you try to operate on the

basis of retaliation.

How do we protect?

Again, what I'm getting at is that the government never said it was going to protect you. And I must make an additional

point here. Because the government

isn't organized to protect you, you are the bait in the trap. You have to be hurt before the government can do anything.

Think how dreadful it would be if

the government acted before the crime by arresting people before they'd

done anything wrong.

I

don't know how many of you have attended a police training session where ordinary, decent

human beings are made into policemen. If you ever attended one of these

sessions, I think you'd find what I am about to say familiar.

The sergeant in

charge of training addresses himself to the men who are called rookies. And he demeans them for a moment, making them feel very bad and then he says, "Now I want you to get

this straight. If you ever do get out of this police academy and become

policemen, your job is to enforce the law

without fear or favor. We don't want policemen here who like some laws and

dislike others. That's not your business. Your business is to go by the book.

You learn what the laws are and you enforce them and you enforce them all the

way up and down the line. Which means if your wife, your mother, your sweetheart, your daughter, or your

best friend is caught violating the law, you book them and bring them

in."

Now,

you will find every policeman taking that training. He's got to take that training to be

a policeman.

POLICEMAN'S DUTY

The

proper relationship between persons is a market relationship which follows

what we call the law of supply and demand. In fields of protection, you and

I are the demanders and we find people who are suppliers who can provide

protection. You go to the store to buy it. The fellow who has the store says.

"My system works. It'll cost you so much, and it

will accomplish this much. I also

have another system that will do this much more and accomplish this much more,

and it will cost you this much more. And this third one works this way,

accomplishes this, and it will cost you this. Which one do you want? My

systems are guaranteed; they will do what we say they will do."

Suppose

you buy a private system, install it and it doesn't work. You can have a

guarantee and you can get your money back. But, notice something. The

man who is dealing with you doesn't look at you and say, "I can't sell

this until I'm sure you're not a crook.

How do I know what you want to do with this device? You can't have it because I have to check upon you. I don't

trust you."

(Using

chalkboard)

Here's

what we get with the government in the picture. Here's the government, and

here are you and me as taxpayers. And we say to the government, "We

want to be protected." The government says, "Sure," and they

hire the police and the police are here. And what do

they tell the police? They say, "You take a look out there where those

taxpayers are and remember that every one of them is a potential crook."

The

police aren't hired to protect you. They're hired to keep an eye on you to see

what you did that was wrong so that they can book you. That's their function.

They are not protectors. They are not hired to be protectors. They are

hired to keep an eye on all of us as potential criminals. Now, do you think they're going to

make you safe? They weren't hired to make you safe.

A

friend of mine has a van and keeps his tools in it. He has rigged it up with a burglar

alarm, by the way. But before he put the alarm, on it, this little event occurred.

He parked it in a parking lot and left it unlocked because he was just

going to talk to somebody right in the parking lot. So the van was unattended

and, of course, he'd left the back door open because he planned to be right there. But

one thing led to another, and he moved several yards away. He looked back as he was engaged in this conversation and a total stranger was lifting one of his cases of tools

out of the van. He ran back and said, "Wait a moment. That's my

stuff."

Right

at this particular time, he happened to see a policeman. So he called for

help. The policeman came over and here was this man holding my friend's set

of tools. And my friend said, "This man just got into my van and helped himself to the

tools."

The

policeman looked at the fellow and the fellow said. "That's not true, officer.

These are my tools. I was walking across the parking lot and this man accosted

me and claimed the tools were his." The policeman said, "Are the tools

marked?" It happened that none of them were. So the policeman looked

around and said, "I don't know which one of you is telling the truth. But

the way I see it, you've got the tools and you

haven't." And the thief walked off with the tools under police protection.

How

did the policeman know who owned the tools? He didn't know. Naturally,

when you're the owner you feel a sense of outrage. But what would you do? Well, since then, my friend has taken care of it. It

isn't going to happen again.

This

is the point I'm trying to make. The police are not hired to protect you. They are there to

enforce the law and what you want is to be safe.

UNIFORM CRIME

REPORT—FBI

What

I have here is a record going back to 1970—the F.B.I. 1970 Uniform Crime

Report. But first, let me show you the 1971 book and these others because I think you

ought to see them.

1971

provides a five-year record. Naturally, those lines don't seem to go up as

rapidly but the reason is this graph provides only a five-year base. And the crime

from 1966 to 1971 went up 83 percent against a population increase of 5 percent.

Now if you double that for ten years, it's approximately the same as the

ten-year chart. Crimes of violence up 90 percent, crimes against property 82

percent; that's the 1971 story. Now, a slight variation once in a while. And the criminologists,

the penologists, the scholars who are studying this are now beginning to tell

us there is a reason for it.

You

notice that in 1972 there was, in fact, a downturn. In 1972 crime in all

categories diminished slightly. Of course, the average for five years is still

up. But that year it declined; it was actually still up on

violent crime but it went down on crimes against property sufficiently

to bring the average down in 1972. That happened once before and the

criminologists said, "We don't understand it; we don't know what caused

it." But now they're beginning to come up with an idea on it. After that

improvement we got in 1972, it almost looks as if the criminals had just taken a

sabbatical and come back with greater enthusiasm than before. Because they

made up for lost time and went right back up to where they would have been

if they hadn't slackened off.

And

I must give you the sad news. This is the last report out, 1976. The 1977 report

comes out in August or September of 1978. They're always behind in Washington.

But

now we have the Carter administration and do you know what they say?

They say, "We are not going to be doing them—the Crime Reports—the same way after

this. Instead of tabulating the known crimes (because we know that they're not accurate), we are just

going to estimate.'' If this is done from

here on, the reports will be worthless. Absolutely. They weren't much good to start with but from now on—zilch. I

wanted you to get that picture. So there

have been a couple of occasions in American history where the crime rate has gone down slightly. What was the extent

of crime in the United States in 1970?

I

have to make a very careful delineation at this juncture. One of the tragic things

that we face all the time is that people tend to equate the law or legislation

passed by lawmakers with what is morally correct. And so there's a

tendency to believe that what is right is what is lawful. And what is wrong is unlawful.

If it's against the law, we assume it's wrong and if it is in harmony with

the law, then it must be all right. Ladies and gentlemen, there's no necessary

connection.

We

have to make a distinction. This is not a distinction made by the F.B.I. But we must make

it. There are types of crime. There are some crimes in which some person was injured as a result of another human being

violating his boundaries in some way,

either his person or his property, and inflicting an

injury by theft, mugging, rape, murder, whatever. So an injury was inflicted. And then there are some crimes that

are merely violations of some legislative

enactment where nobody was injured at all except perhaps the dignity of some piece of paper. That's all. Now,

the government doesn't make a great deal of distinction here.

There

are various categories but when it comes to, for example, the difference

between a bank robber and a man who doesn't pay his taxes; the government sees

no significant difference. The government will tell you a man who

doesn't pay his taxes is essentially a thief. He is robbing the government. Now,

that's the government's point of view. I don't happen to share it and I don't

think many of you do. But that is actually what they will say so they will treat

a tax evader with exactly the severity they would a bank robber. From their

point of view, he's done the same thing. He has taken money belonging to

others. Okay, now, I wanted to get that into the record because of these two very

definite classes of crime, the class of crime where there are injuries and the class of crime

where crimes are crimes only because the government says they are.

THE

CRIME REPORT

Going

back to the 1970 book then, let us list the kind of crime that we had and the

cost in terms of dollars, in the United States. The total cost of crime, according

to a study that was performed by U.S. News and World Report in 1970—and

there has been no composite study of equal merit since then—the total cost of crime

in that year was $51.1 billion.

I'm going to make the breakdown I told you about.

First. I'm going to talk about

real crime where injuries are inflicted. The largest category in the United

States is business theft; that is to say, theft from employers performed by their employees—that's the number one

category. And it has been for a

number of years and it is the number one today. This is a sad commentary on what is happening in this nation. There

is such, an anti-business, anti-capitalist mentality in the land that a

businessman is viewed as fair game by a

great many of his employees. They simply take advantage of him at every opportunity. And they don't think it's

wrong. Some of it is petty. They will

steal a few stamps, some pencils, paperclips. They put a little gas into the car from the company pump and they don't report

it. They pad their expense accounts. In fact, that's almost a new form of

literature in the United States, the

padded expense account. They do anything and everything against the boss and they think nothing of it. If you work for

a grocery store, you take out a half

a ham or half a case of peaches, stick it in the car. If you work at a machine shop, you take a few tools or maybe a few

machine parts. And it goes on and on.

Additionally, we've actually found whole rings of thieves professionally operating within given plants and just

fencing the material the firm is

making or handling. Business theft is a big item. And it was the largest in the United States in 1970. The figures today would

be larger but then it was $3 billion.

All of these numbers will be in billions of dollars.

The

second largest crime in 1970 was homicide, $2.1 billion. Now, how is that

figured? Obviously, one cannot calculate the value of a human life accurately. Nobody said these figures were

accurate. The victim's earning power

based on his educational background or his business experience, whatever it may

have been is estimated. Then "the loss to society" from the date he was eliminated is calculated. Thus, if a person

was relatively young at the time he was

murdered, the loss to society is great. If he was past 65—boys will be boys. Of course, now it's going to be past 70 because

they're changing retirement laws. But that's the general idea, so the

loss is calculated dollar-wise based on the

anticipated earning power of the deceased. To which is added hospitalization costs in the process of becoming

deceased or any insurance payouts which are also added. It came to $2.1

billion. (Q. Do your figures include

court costs? A. No, that's separate. I'll show them as I have them.)

Robbery

and burglary, listed as a single crime, came to $2 billion. Of course, business theft is

also robbery and burglary but it's separately classed.

Then we have drunk

driving. Not that the driving is the problem. It's stopping in the wrong way. And when that happens it can be a very costly

affair. Not only automobile damage but manslaughter and other property damage is included here, $2 billion. Then we have

fraud and embezzlement, and that's

$1.5 billion. And we have vandalism, $1.1 billion. Hijacking is $900 million. And shoplifting is $500 million. Notice,

most of these are theft or robbery of one kind or another, but they give them

special categories. And this, of course, adds up to $13.1 billion.

You

will notice that they have not included mugging or rape. The reason is that

they couldn't figure out how to put a dollar value on them. So we don't have

it in dollars. The F.B.I, keeps an eye on it, but we don't have a dollar value,

so take a mental note. It's bigger than this by the cost of those particular crimes.

So

that is the total cost of crime where there were victims as opposed to the

total cost of crime. I submit that those numbers are widely apart, $13.1

billion as

opposed to $51.1 billion.

Now,

let me show you where the government feels the big problem is. You're

going to love this first one. Gambling: number one crime in the United States.

Oh, not just gambling—illegal gambling. This doesn't include Los Alamitos

or the state of Nevada: anything that's legal doesn't count. This is illegal

gambling. Hang on. Fifteen billion dollars—bigger than all of these put together.

Bribery of officials, $5 billion. (Q. Does that include government officials?

A. These are the only ones that are reported.) Obviously, it's bigger than

this, but these are the only ones that have been reported. I'm sure I don't have

to tell you if the officials weren't there, you wouldn't have to bribe them.

Who

was it? Professor Buchanan, University of Virginia, has done a study showing

that if you had a government in which bribery became impossible, nothing

would work. You have to be able to bribe government people to get the

wheels to turn around because they've so many legislative enactments that

freeze everything shut you have to grease the wheels. Fortunately, we are not likely to

run into that kind of government where bribery doesn't occur. You just have to

be careful.

Narcotics,

$2.2 billion. All of these figures are dated. They go to 1970. Let me pause

for a moment to take up this question of narcotics because I would be very

happy to be on the record with you as being strongly opposed to the use of hard

drugs. I think hard drugs are bad news. And I would like to see this practice of using

hard drugs reduced as rapidly as possible. Therefore, I must urge that we get

the government out of this area as fast as we can in order to control it. Here

we have a very serious problem.

DEMON RUM & THE

18th AMENDMENT

Ladies

and gentlemen, there is no reason for us to be confused in this area. We,

of all people, have had experience. And it should have come to our minds when

we were getting all uptight in this area a matter of ten, fifteen, twenty years ago.

May

I recite just a very little history of the United

States? Earlier in this century, during the 'Teens, a group of very

well-intentioned ladies decided that

alcohol was a dangerous substance and it ought to be forbidden. The men of the country were too weak-willed to resist the

temptation of demon rum. Therefore a law would have to be passed to protect

their helpless wives and children. For the husbands were getting paid on

Saturday, stopping at the saloon on the way

home, and then the rent money wouldn't arrive home with them.

Therefore, to

protect the helpless wives and children, a law would be passed to prevent the manufacture, sale, and distribution of alcoholic

beverages. Now, these ladies were, of course, marvelously well intentioned.

And there's no question but that

alcohol is a dangerous drug. It is not a food. It is a preservative. When you drink it you do not get

nourished, you get pickled. That's the way it works.

So

the ladies decided to do something about it and they raised quite a bit of

money and made quite a bit of noise. In process, they were joined by another

equally splendid group of men, a ministerial organization, who likewise went out

and thumped the drum to get money and to get the 18th Amendment passed, while

they were in the midst of this brouhaha getting everything revved

up, what should happen but a nice supply of money came in from out of the

country. And they were able to put the whole thing across. The 18th Amendment was

ratified in 1918.

Where

do you think that nice lump of money came from? It came from Sicily.

Why do you suppose the people in Sicily wanted to see us ratify the 18th amendment?

Well, it's called profit. You see, if you can get an addictive drug—and

alcohol can be an addictive drug—forbidden, against the law, then there

are people—we sometimes refer to them as Mafia, or the Syndicate, or whatever

affectionate term we have for them—who don't mind breaking the law.

A legitimate businessman does. If you make alcohol illegal, the legitimate

businessman goes out of business and the Mafia comes in. And they don't

mind dealing with the police; they either bribe them or shoot them. To the

Mafia it's a matter of indifference either way. So the policeman is handled and

now the one thing the Mafia can't handle he doesn't have to. The government's

handling it for him. The thing the Mafia can't stand is competition. But the

government can handle the competition so the Mafia would like to have it that way.

With no competition, they come in.

I

see that there are probably a number of people in the audience tonight who can

remember the happy days that followed the ratification of the 18th amendment. I

was around at the time and I presume some of you may have been.

Let me just remind you that prior to 1918 we had, in the United States, one of

the lowest per capita consumption rates of alcohol in the world, one of the

lowest. We were, indeed, a sober nation. Our sobriety was almost Victorian. We were, really,

a little bit prissy in that area.

But

let me remind you what the situation was. Saloons were almost as plentiful

then as filling stations are today. The "corner" saloon. You didn't say

the saloon, you said the corner saloon because the chances were good that there

was a saloon every few blocks. It was on the corner where you could get at it

from either direction fast. Now, what about the liquor that was sold in the saloons?

In

those days you could go into the corner saloon and for five cents you could buy

a bucket of beer, the finest brew made, and while you were drinking it the bartender

would have sandwiches on the counter and pretzels and peanuts. And

you helped yourself and there was no charge. If a man had as much as a nickel, he could

get full.

You

know, people, in those days we didn't have much of a welfare problem. A

man could always panhandle a nickel even if he was broke. You could go out on

the street and say, "Sir, could you spare a nickel or a dime?" And

you could get fed with that. But you could also get drunk

with it. What about whiskey? The finest whiskey available: rye, scotch, bourbon—ten cents a

shot. Back then it was readily available. In every corner saloon, a nickel for all the beer you'd want to hold, well, all the

beer I'd want to hold—more than I'd

want to hold to tell you the truth—and hard liquor, ten cents. And we had one of the lowest alcoholic consumption rates in

the world.

Okay

now, in 1918, the amendment, the Volstead Act, and the enforcement teams

come out. And from 1918 to 1933 and 1934 when the Act was repealed, what

happened? We went from one of the lowest per capita consumption rates

in alcohol to one of the highest in the world while the government was

suppressing it. Now', people, if you don't understand that, see me after we're through

tonight. I mean, this is so conspicuous that it should have warned us.

What

about hard drugs? In 1960 a survey was made to discover the rate of hard

drug addiction in New York City versus London. The two cities are huge: they

were comparable in size at that time. I believe they still are. At that particular

time, in I960, in London there were no laws whatsoever against the taking of hard drugs. In London, a person could go into any

chemist's—that's a drug store — and

for one shilling could buy six fixes of heroin, the pure stuff, uncut. And for your information, not that I have

to tell some of you, but with six

fixes of uncut heroin you can go into orbit for a month. You don't even have to

touch the landing strip. And that's a shilling. Now, how many drug addicts did they have in London when hard drugs were readily available? It was not viewed as a crime

and anybody who wanted it could get

all he wanted for a shilling. At that particular time, according to the figures,

there were 200 drug addicts in London.

THE NEW YORK CITY

ADDICTION

Let's

compare that with New York. In New York City, and for nearly a hundred

years prior to this time, this goes back to the 19th century in our case, we've

been fighting hard drug traffic that long. The Treasury Department, the

T-men, had been given the task of trying to suppress trade in whatever drug

the government says is banned. And this, of course, included hard drugs right

from the beginning. And hard drugs are bad news, no question. So the Treasury

men had been fighting it and they had been fighting it for years and spending

millions of dollars in suppressing it. And in 1960, when the survey was

made, in New York City there were more than 14,000 drug addicts.

Now,

how could a person get the drug in New York City? The only way was from

your friendly neighborhood pusher, who was, of course, tied in, directly or

indirectly, with the underworld. What would it cost? Well, it depended on what

the pusher thought he could get. He might charge $25 for three fixes of

questionable quality that might have been cut with a strychnine, so you didn't know

what you were getting. Or he could charge $30 or $50 or $100, depending on what he thought

he could get out of you.

At

that price a person can't go out on the street and say, "I need a fix. Can

you let me have 50 bucks?" You might be able to panhandle a nickel or a

dime, but you can't go up to someone and say, "You know, I'm having a problem" and

get that kind of money.

So

what happened? Well, you not only have over 14,000 addicts in New York, but

according to the figures that have been released, 60 percent—that's the figure

they gave me, I don't know that it's accurate but that's what they tell me—sixty

percent of the crimes with victims are drug - connected. Why? Because when

someone gets hooked on hard drugs, he can't earn his own living.

And when he comes out of his stupor and effects a landing, as it were, he has to get back

into orbit as fast as possible. He has a craving that is enough to make the strongest man scream for help.

It's a terrible thing and he'll do

anything to support the habit. He can't earn the money so what will he do?

Literally anything. In fact, a good many of the heavy crimes we are getting today, unquestionably, are drug-connected.

So he'll steal purses or slit throats, take hubcaps or automobiles, smash

windows, set fire to buildings,

anything that he can do to get his hands on that kind of money. And this is the figure—60 percent—drug connected. So that's

why I said what I did. There is no

justification whatever for allowing the government to get into this area, as sensitive as it is. And, of course, the

hard drug thing is a bad scene. We've got to get the government out of

there so we can handle it.

Let's

go to the next item. This is the illegal manufacture of alcohol. I see it's still

a business and it is charted at $770 million. A good deal of the illegal alcohol

today is manufactured in the Carolinas and Georgia by the moonshiners. They're

still operating there as they did during' prohibition days. Why is it illegal? You want to know the reason?

There's only one. These fellows won't pay taxes, that's all. They're

simply evading alcohol taxes. These are tax

evaders, but they're listed as criminals. They're moonshiners. They're

bad people, quote unquote, because they're not paying their taxes. They are manufacturing alcohol and selling it

without paying the tax. I can't tell you how good or bad it is. I

haven't sampled it.

Okay.

Next item. Illegal interest charges, $500 million. Now, ladies and gentlemen, loan

sharks can be tough. But so far, the record is overwhelmingly clear. Loan sharks have never been known to

go after anybody who hasn't borrowed

from them. If you would like to stay out of the clutches of a loan shark, that's entirely within your capacity.

Don't borrow from them. So I'm not too impressed with the idea that these

people are criminals. Oh, sure they are very rough, but you know, if you

go to them, you're asking for trouble. And

I'd recommend that you not go unless you pretty well know what you're

doing. Then if it doesn't work out right, don't come crying to me.

Then

we have prostitution, $400 million. I understand it's enlarging again. It went way down

although it used to be big.

And

then they list tax fraud. I know this figure has to be wrong but they say $100 million. They

don't want to tell you how big it is.

And

that comes to $23.9 billion. Ladies and gentlemen, those crimes listed here

are crimes because the government says they are. And it's larger by $10 billion

than crimes where people get hurt. These two figures added up still don't come to $51.1

billion.

But,

now, you asked a question about court costs and so on. Here's where they come

in. In addition to these losses, the police departments around the country

cost $5 billion. Penal institutions cost $1.0 billion and the courts cost another

$1.8 billion for a total of $8.6 billion. That still doesn't add up.

The

other $5.5 billion, ladies and gentlemen, was spent by those who finally, beginning

apparently about 1972, began to realize that the police didn't protect them

and weren't going to. So they went out into the market and began protecting

themselves. And that worked. Now, I'm not selling subscriptions to these. They're probably good. These are two

magazines and they're put out right

in this area, the Los Angeles area, Security World and Security Distributing

and Marketing magazines.

Both of these are filled with ads and articles that tell you how to protect your life, your property,

your person by going into the market and getting the job done.

And

what do the insurance companies tell us about this? They tell us if you will

protect yourself and not wait for the police, that, in many cases, they can

lower your insurance rates because the evidence shows that when people are alert to the

problem and protect themselves that private protection is about 90 percent effective. Government protection is 80

percent ineffective. And, people, that's a broad, broad, difference.

If

you rely on the police you have a 20 percent chance and if you rely on yourself and go to

the marketplace you have a 90 percent chance. Now, nothing's perfect. Many times this is my most serious difficulty in

trying to explain what government does in this area.

The

American people have been deceived so often that they expect me to offer them a

panacea in which I give them a written guarantee that all they have to do is go

to the marketplace and no crimes will ever happen again. That's baloney and I

know it and you know it and I can't give you any guarantee. But the government did, you see, or at least many people

think the government did. What the

government said was, "Trust us and we'll handle it for you." That made it possible for you to

forget all about it. You presumed that

the government was going to handle it for you. They can't handle it. They haven't been handling it. But I am not going to

fool you. The government has gotten many of you to believe they're

taking care of the problem. They're taking

care of nothing. You are vulnerable, but if you'll go into the private area,

you can move significantly in the direction of your own protection.

GOVERNMENT IS AN

INSTRUMENT OF VENGEANCE

Now

here is where the hang-up is. If you are still concerned with retaliation and

want to get after the fellow who, despite your best efforts, breaks in and

steals from you, then you are going to have to have a government. Government

is an instrument of vengeance. That is all it is and that is all it has been from

the start. Of course, I repeat, if you protect yourself and if you are protected

in fact, then you're safe. And the question of punishing someone for hurting

you can't come up because you weren't hurt. That's what you want. If you can't

think that way, and I have found many people who really can't, then you have a

problem. Some can't think protection. They can only think retaliation.

I can't say to them, "Go into the market and I'll guarantee that there

will be no more crimes." Then they say, "A crime is

apt to happen." And I'll say, "Yes, that's true. Any crime is still

apt to happen. I'm talking about reducing it from its present level by a tremendous

factor." And they say, "Well, a crime could still

happen," Yes, that's right, it could.

But

what do you do with the guy who did it? Well. I don't know. What do

you want to do with him? My

suggestion would be this. If you buy a lock for your door and somebody breaks

it, buy a better lock. You aren't going to know who did it any more than the police. So all of your worry

about how to get even is predicated

on the idea that somehow: 1) You know who did it; 2) You can catch him; 3)

You're bigger than he is; and 4) You can beat it out of him. Well, people, you're chasing a mirage. It isn't going

to happen. But you don't have to worry about it if you'll start thinking

in terms of protection.

If

we were to get rid of the government—not that we can. Certainly we can't

do it overnight. But just let your minds flow free for a moment. Let us suppose

that, by some magic process, we could eliminate the government overnight. These

costs would disappear.

The

costs of government retaliation would vanish. That's $8.6 billion. Then the

costs of retaliating against those who offend legislative enactments would vanish.

That's another $23.9 billion. The cost of retaliation against victimless crimes.

When it comes to crimes with victims, they could be reduced. The figures I have say

that 60 percent of these crimes are drug connected.

EXAMPLE: COMMUNITY

A & B

Now

we could reduce this figure. I'm not

going to tell you 60 percent. That's a government figure and I question

it. But let's suppose we cut this by a substantial

amount. Let's suppose we cut this, say, by $3 billion. And we were left with a $10 billion problem. So we have a $10

billion problem. Let's suppose we

have to double private protection costs in order to protect ourselves. That would give us $11 billion and we have moved, by

the simple process of getting government

out of the way, from a $51 billion problem to a $21 billion problem. You still have a problem, but I don't think

that's bad for openers. That would

just get it started. You could reduce it from there. This is the example I was

leading up to. Let us suppose that we have two communities. Community A and

Community B, in the United States. And they're identical in all respects except one. Let me presume, for purposes of

comparison, that both of these communities

have 100,000 population, 25,000 homes and 5,000 businesses. And they're

equally attractive or unattractive depending on what you think of cities of 100,000. So, they're alike in all

respects save this. Town A has a city manager

and a mayor and a city council and the constabulary, the police force, the jails, the courts, the judges, the

laws, the works. What we would typically

expect today is an American town of 100,000. And Town B is the same

except it doesn't have any of those customary legal trappings.

What

would we have in Town A? In Town A, ladies and gentlemen, how many

police would there be? If we take the national average, we will discover,

as of now, about 175 police in Town A that has a 100,000 population, including

meter maids. That means that we have 175 people working round the

clock, three shifts a day. We have to allow for vacations and illness. We would

do well to have 50 people on duty at one time. And you're asking those people

to protect 100,000 people, 25,000 homes and 5,000 businesses. The problem

is absolutely insurmountable. It can't be done. That's an absurdity.

But

there's something else. Last year, in the average town of 100,000 in the United States,

9,000 pieces of real estate were sold to pay the taxes that provide the basic cost for the police. That was

the biggest rip-off in that community,

the loss of 9,000 pieces of real estate to pay the various tax-supported

agencies including the police.

If

you were to go to this community and add on to the police department the numbers

of personnel required to perform an adequate job, you'd end up confiscating

all the rest of the real estate and you'd shut the town down. You have

a system here that is so bad that as you improve it, it gets worse. Let's see what else you

have in Town A.

The

police department, ladies and gentlemen, is the best advertised of any

governmental agency. There will be no newspaper issued that will not recite their exploits. If

you watch television, every major television station will have at least one

drama every day in which the police are the heroes. And they are handsome and they are loving and they are kind and they are

good. They are trustworthy, loyal, friendly, helpful, courteous,

thrifty, brave, clean, and reverent. And

they get their man and we love them. And that goes on day after day and in

color and in your living room. So you are exposed to that. So we know about the

police. They have, what we would call, a high profile. You know about them. They are there. And the result? Let me

tell you. You pay a lot of taxes for

them and you know that, too. You're convinced the police are there; you're paying for it; you hear about the police

all the time.

OUR

PROFESSION IS UNDERSTAFFED

So

what do you do? Well, I'll tell you what you do. You go to bed one night without

locking your front door. And you get up in the morning and you don't even know

the door's been unlocked until you start to leave for work. You go to

the door and, my gosh, it was unlocked all night. You start out and there is your

car at the curb. You planned to put it in the garage but the kid's tricycle was

in the driveway so you pulled in front. You were going to go back later but you

didn't; you forgot. So, okay, at least the car's there. So you walk down and as

you get to it, you're feeling in your pockets and you can't find your keys. And

you look at the car and dangling from the ignition are all your keys. You

pulled them out a little to break that noise

because it bothers you. And your keys

have been in the ignition in front of your house all night and nothing happened. And you say, "It's a good thing

we've got the cops because if it weren't for them, I sure would have been

ripped off." That is exactly what happens. You begin to live in a

fool's paradise. You think you are safe.

I

have an article written by a burglar who wrote the item while he was serving time in the

Missouri State Penitentiary. More on that, if you're interested.

I'll tell you how he happened to get there. He got

there by design. And he says,

"If you haven't been ripped off recently, don't credit the police."

He says the reason is: "Our

profession is understaffed." He says the American people are simply inviting the burglars and

"We don't have enough people to take care of the opportunities." But

he says "Don't worry. We'll get around to you in time. Our fellows are working nights." You know, trying to

catch up. So obviously the burglar

knows what he is talking about. He's a pro. He says that a

professional burglar rarely has to break in.

You

don't break. You just walk around and try the doors. And about one in five

will be unlocked. So you open it and walk in. You don't ring the bell; you walk

in and when you get inside you say, "Hi, Maude. I'm here." And you wait. The likelihood of

Maude being there is very remote because probably there is no Maude. You pick a name like that, you

see. There aren't many Maudes anyway

but the likelihood of Maude being there is very remote. But what if somebody is

home? They come to the door. And here's a strange man standing just inside the door. And the first

thing the crook says is, "Where's Maude?"

The lady of the

house says, "There's no Maude here."

He says,

"Well, where is she? When is she coming back?"

"Well,

no Maude lives here."

"Oh, really?

Maude Jones?"

"There's

no..."

"Well, ma'am,

excuse me, but isn't this 122 Maple Street?"

"No,

this is 122 Elm."

"Oh,

I beg your pardon. I've been away for a year. I used to live in this neighborhood

and I moved away a long time ago. And I've got the streets mixed

up. I hope I didn't startle you. Excuse me, please." He leaves. Do you think that's going

to be reported as a crime?

This

is how it's done. But what if nobody's home? Ha. This man is a pro. He knows

where your stuff is. First thing he does, he gets one of your suitcases. He

doesn't carry one. He knows where you're going to keep yours so he takes that,

zip, zip, zip. He gets stuff in it and he goes sauntering out of the house. And

if anyone asks him, he's going to meet you. You forgot something. He's got

your bag to prove it. You really think he's going to be caught? Nobody was there. He made sure

of that to begin with. How does he make sure?

Do

you know what a crook can do? He goes down to the local police station, provides

a card showing that he's a member of a national writers association and

says he's doing an article studying police methods. And he'd like to bone up

on the police methods that are employed in the local town. He'd like to ride around

in the black-and-whites, get to know the officers, and see just what they do. They'll tell him. They'd better; he's a

taxpayer, isn't he? He learns all

about how the locals work. I'm

speaking of a pro. I'm not talking

about amateurs now; they get into

trouble. The pros know what to do. They meet the policemen. They find out what the police beats are. They know where the

cars are. They time it. They know

how long it will take for a radio response. And you wonder why the police are

only 20 percent effective? I marvel they get results at all. What they catch is

the amateur who doesn't know how to do it. Well, this burglar explains

this.

Of

course, once in a while he would get greedy enough so he would break in. And

he told about one place where he thought the pickings would be good enough

to warrant breaking in because the story was that there were plenty of

goodies inside. But when he went to the house in a very nice neighborhood he

discovered that the people inside had anticipated that somebody might show up. And guess

what they had done?

They

had put bars on all the windows, ornamental bars, quite attractive, but

they were there. Now, you know that's an interesting point. We seem to have complete

confidence that after a man has committed a crime we can arrest him, put him behind bars, and he can't get

through them. It's true. But

if you put the bars in front of

him, he can't get through them, either. And if he doesn't get through them, then he can't commit the crime.

So the same process will prevent the crime

rather than trying to take care of it after the fact. These people had

anticipated that so he couldn't get through the windows.

He

checked the door. The average door on the average house can be opened with

a credit card. And everybody has one of those, at least one. Most doors don't

have good locks. That is, they have the convenient lock which is the night

latch. But you can buy for a relatively few dollars a good bolt action lock.

If you're worried, buy two and put them on the same door. If you're really

worried, buy four and put them on the hinge side as well as the latch side and one top

and bottom.

And

then, if you really want to be sure, you know most doors are just plywood

with air between and you can get through both of them with your fist. Put

on a glove and “bing” you're right through. But for a very small amount of money

if you have any mechanical ability, take down your doors, take off the top

strip of wood, and you can buy these metal rods that are used to reinforce

concrete, and you weave that into a network, a grid, and stick it in your door.

Then go to the sawmill and have them blow sawdust mixed with glue in there and

fill it up. And if anybody hits that door with his fist, he's going to break

his arm. Put that in. It's going to look exactly

as it did before. It looks like a plywood door. And heaven help the man who runs into it because whatever contacts it is going to be hurt. And now you put

it up with good locks and nobody's

going through it. Well, that's exactly what this burglar found. These people had fixed their doors. He couldn't

get through the doors and he couldn't get

through the windows but there was still

a chance.

It

was a two-story house and the window on the landing halfway up didn't have

bars. So he stashed a box in the alley. A ladder, you know, would have been too

much of a giveaway. And a box was just about the right size. So he waited

until he saw his victims leave. He got his box, stood under the

window: it was just the right height

so he could reach the window. And he'd come prepared. I perhaps ought to charge an added fee for some of this

information. Anyway, you take

masking tape and you put a couple of strips, zip, zip, across the glass leaving a loose part in the

middle so you can control the glass. You

have a glass cutter, zip, zip. You take out the glass—doesn't make any noise—set it down and now the crook is ready to

crawl in.

He

started through the window and looked up. He was at a landing as he had anticipated.

At the top of the stairs a pair of cat's eyes were looking at him in the

dark. The only trouble was they were eight inches apart. His first thought was. Well, what do you know? A pair of one-eyed

cats. He had a little pocket flashlight, turned it on, and there was a black

panther looking at him. The panther was chained, he said. He wasn't and

left. Now, that's protection.

NOBODY'S

BEING PROTECTED

I'm

not trying to boost the stock of black panthers. The fact is that these people

had realized they didn't have any safety with the police and so they had done what

seemed intelligent to them. They had successfully turned aside a professional. But you don't have to go to

this extreme. You can accomplish the

same objective if you use your head. And for goodness sakes, don't

expect the police to protect you because they're not going to.

A

friend of mine used to travel a good deal and left his wife behind. One day she

was at home in her house. She was upstairs but the phone was at the foot of the

stairs and the downstairs was dark. The phone rang and she went down the stairs to

answer it. Looking through the darkened room and out of the window, she saw a