NO TREASON.

No. 1.

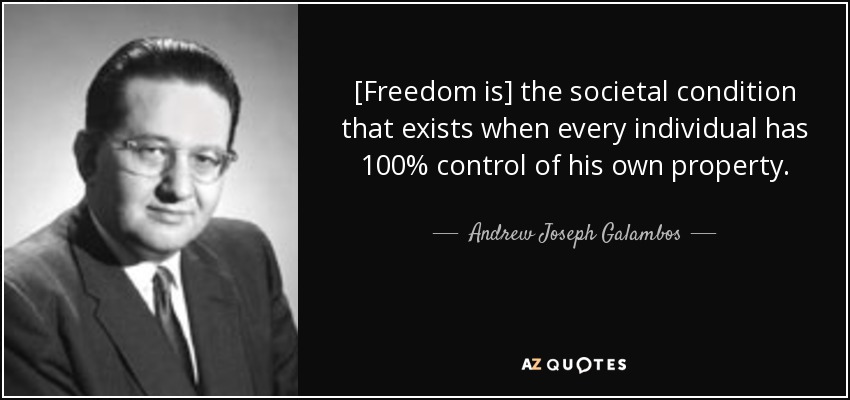

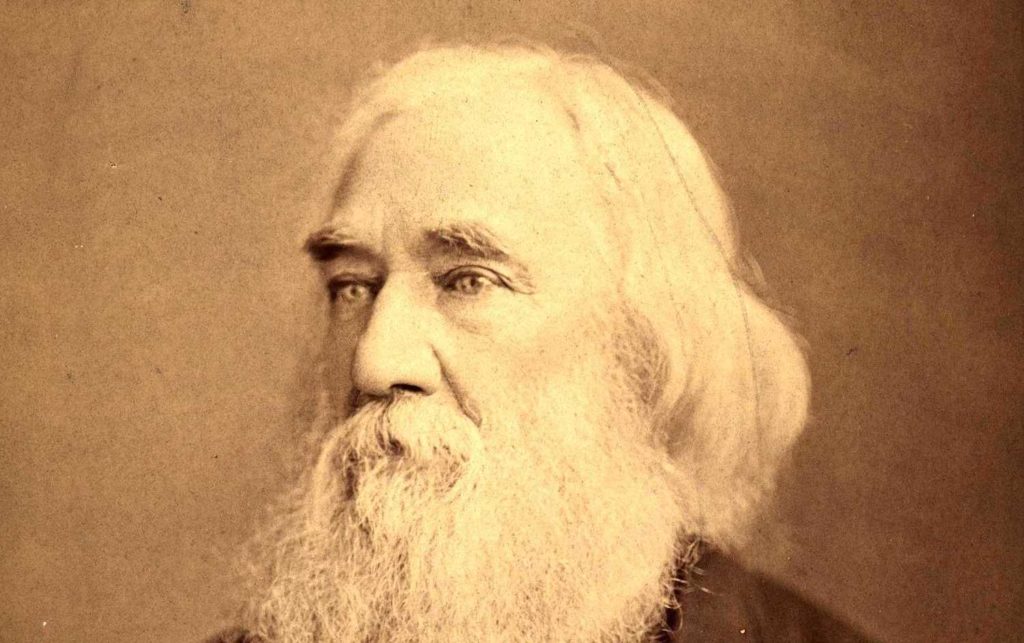

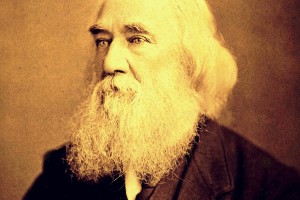

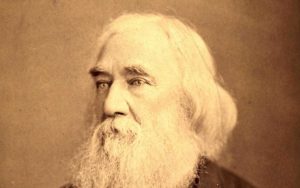

BY LYSANDER SPOONER

Would you like to enjoy “No Treason” on audio? Click HERE for the free audio version at mises.org.

BOSTON:

PUBLISHED BY THE AUTHOR,

No. 14 Bromfield Street.

1867.

Entered according to Act of congress, in the year 1867,

By LYSANDER SPOONER,

in the Clerk’s office of the District Court of the United States, for the District

of Massachusetts.

[*iii]

INTRODUCTORY.

The question of treason is distinct from that of slavery; and is the same that it would have been, if free States, instead of slave States, had seceded.

On the part of the North, the war was carried on, not to liberate slaves, but by a government that had always perverted and violated the Constitution, to keep the slaves in bondage; and was still willing to do so, if the slaveholders could be thereby induced to stay in the Union.

The principle, on which the war was waged by the North, was simply this: That men may rightfully be compelled to submit to, and support, a government that they do not want; and that resistance, on their part, makes them traitors and criminals.

No principle, that is possible to be named, can be more self-evidently false than this; or more self-evidently fatal to all political freedom. Yet it triumphed in the field, and is now assumed to be established. If it really be established, the number of slaves, instead of having been diminished by the war, has been greatly increased; for a man, thus subjected to a government that he does not want, is a slave. And there is no difference, in principle — but only in degree — between political and chattel slavery. The former, no less than the latter, denies a man’s ownership of himself and the products of his labor; and [*iv] asserts that other men may own him, and dispose of him and his property, for their uses, and at their pleasure.

Previous to the war, there were some grounds for saying that — in theory, at least, if not in practice — our government was a free one; that it rested on consent. But nothing of that kind can be said now, if the principle on which the war was carried on by the North, is irrevocably established.

If that principle be not the principle of the Constitution, the fact should be known. If it be the principle of the Constitution, the Constitution itself should be at once overthrown.

[*5]

NO TREASON

No. 1.

I.

Notwithstanding all the proclamations we have made to mankind, within the last ninety years, that our government rests on consent, and that that was the rightful basis on which any government could rest, the late war has practically demonstrated that our government rests upon force — as much so as any government that ever existed.

The North has thus virtually said to the world: It was all very well to prate of consent, so long as the objects to be accomplished were to liberate ourselves from our connexion with England, and also to coax a scattered and jealous people into a great national union; but now that those purposes have been accomplished, and the power of the North has become consolidated, it is sufficient for us — as for all governments — simply to say: Our power is our right.

In proportion to her wealth and population, the North has probably expended more money and blood to maintain her power over an unwilling people, than any other government ever did. And in her estimation, it is apparently the chief glory of her success, and an adequate compensation for all her own losses, and an ample justification for all her devastation and carnage of the South, that all pretence of any necessity for consent to the perpetuity or power of government, is (as she thinks) forever expunged from the minds of the people. In short, the North [*6] exults beyond measure in the proof she has given, that a government, professedly resting on consent, will expend more life and treasure in crushing dissent, than any government, openly founded on force, has ever done.

And she claims that she has done all this in behalf of liberty! In behalf of free government! In behalf of the principle that government should rest on consent!

If the successors of Roger Williams, within a hundred years after their State had been founded upon the principle of free religious toleration, and when the Baptists had become strong on the credit of that principle, had taken to burning heretics with a fury never seen before among men; and had they finally gloried in having thus suppressed all question of the truth of the State religion; and had they further claimed to have done all this in behalf of freedom of conscience, the inconsistency between profession and conduct would scarcely have been greater than that of the North, in carrying on such a war as she has done, to compel men to live under and support a government that they did not want; and in then claiming that she did it in behalf of the of the principle that government should rest on consent.

This astonishing absurdity and self-contradiction are to be accounted for only by supposing, either that the lusts of fame, and power, and money, have made her utterly blind to, or utterly reckless of, he inconsistency and enormity of her conduct; or that she has never even understood what was implied in a government’s resting on consent. Perhaps this last explanation is the true one. In charity to human nature, it is to be hoped that it is.

II

What, then, is implied in a government’s resting on consent?

If it be said that the consent of the strongest party, in a nation, is all that is necessary to justify the establishment of a government that shall have authority over the weaker party, it [*7] may be answered that the most despotic governments in the world rest upon that very principle, viz: the consent of the strongest party. These governments are formed simply by the consent or agreement of the strongest party, that they will act in concert in subjecting the weaker party to their dominion. And the despotism, and tyranny, and injustice of these governments consist in that very fact. Or at least that is the first step in their tyranny; a necessary preliminary to all the oppressions that are to follow.

If it be said that the consent of the most numerous party, in a nation, is sufficient to justify the establishment of their power over the less numerous party, it may be answered:

First. That two men have no more natural right to exercise any kind of authority over one, than one has to exercise the same authority over two. A man’s natural rights are his own, against the whole world; and any infringement of them is equally a crime, whether committed by one man, or by millions; whether committed by one man, calling himself a robber, (or by any other name indicating his true character,) or by millions, calling themselves a government.

Second. It would be absurd for the most numerous party to talk of establishing a government over the less numerous party, unless the former were also the strongest, as well as the most numerous; for it is not to be supposed that the strongest party would ever submit to the rule of the weaker party, merely because the latter were the most numerous. And as a matter of fact, it is perhaps never that governments are established by the most numerous party. They are usually, if not always, established by the less numerous party; their superior strength consisting of their superior wealth, intelligence, and ability to act in concert.

Third. Our Constitution does not profess to have been established simply by the majority; but by “the people;” the minority, as much as the majority. [*8]

Fourth. If our fathers, in 1776, had acknowledged the principle that a majority had the right to rule the minority, we should never have become a nation; for they were in a small minority, as compared with those who claimed the right to rule over them.

Fifth. Majorities, as such, afford no guarantees for justice. They are men of the same nature as minorities. They have the same passions for fame, power, and money, as minorities; and are liable and likely to be equally — perhaps more than equally, because more boldly — rapacious, tyrannical and unprincipled, if intrusted with power. There is no more reason, then, why a man should either sustain, or submit to, the rule of the majority, than of a minority. Majorities and minorities cannot rightfully be taken at all into account in deciding questions of justice. And all talk about them, in matters of government, is mere absurdity. Men are dunces for uniting to sustain any government, or any laws, except those in which they are all agreed. And nothing but force and fraud compel men to sustain any other. To say that majorities, as such, have a right to rule minorities, is equivalent to saying that minorities have, and ought to have, no rights, except such as majorities please to allow them.

Sixth. It is not improbable that many or most of the worst of governments — although established by force, and by a few, in the first place — come, in time, to be supported by a majority. But if they do, this majority is composed, in large part, of the most ignorant, superstitious, timid, dependent, servile, and corrupt portions of the people; of those who have been over-awed by the power, intelligence, wealth, and arrogance; of those who have been deceived by the frauds; and of those who have been corrupted by the inducements, of the few who really constitute the government. Such majorities, very likely, could be found in half, perhaps nine-tenths, of all the countries on the globe. What do they prove? Nothing but the tyranny and corruption of the very governments that have reduced so large portions of [*9] the people to their present ignorance, servility, degradation, and corruption; an ignorance, servility, degradation, and corruption that are best illustrated in the simple fact that they do sustain governments that have so oppressed, degraded, and corrupted them. They do nothing towards proving that the governments themselves are legitimate; or that they ought to be sustained, or even endured, by those who understand their true character. The mere fact, therefore, that a government chances to be sustained by a majority, of itself proves nothing that is necessary to be proved, in order to know whether such government should be sustained, or not.

Seventh. The principle that the majority have a right to rule the minority, practically resolves all government into a mere contest between two bodies of men, as to which of them shall be masters, and which of them slaves; a contest, that — however bloody — can, in the nature of things, never be finally closed, so long as man refuses to be a slave.

III

But to say that the consent of either the strongest party, or the most numerous party, in a nation, is sufficient justification for the establishment or maintenance of a government that shall control the whole nation, does not obviate the difficulty. The question still remains, how comes such a thing as “a nation” to exist? How do millions of men, scattered over an extensive territory — each gifted by nature with individual freedom; required by the law of nature to call no man, or body of men, his masters; authorized by that law to seek his own happiness in his own way, to do what he will with himself and his property, so long as he does not trespass upon the equal liberty of others; authorized also, by that law, to defend his own rights, and redress his own wrongs; and to go to the assistance and defence of any [*10] of his fellow men who may be suffering any kind of injustice — how do millions of such men come to be a nation, in the first place? How is it that each of them comes to be stripped of his natural, God-given rights, and to be incorporated, compressed, compacted, and consolidated into a mass with other men, whom he never saw; with whom he has no contract; and towards many of whom he has no sentiments but fear, hatred, or contempt? How does he become subjected to the control of men like himself, who, by nature, had no authority over him; but who command him to do this, and forbid him to do that, as if they were his sovereigns, and he their subject; and as if their wills and their interests were the only standards of his duties and his rights; and who compel him to submission under peril of confiscation, imprisonment, and death?

Clearly all this is the work of force, or fraud, or both.

By what right, then, did we become “a nation?” By what right do we continue to be “a nation?” And by what right do either the strongest, or the most numerous, party, now existing within the territorial limits, called “The United States,” claim that there really is such “a nation” as the United States? Certainly they are bound to show the rightful existence of “a nation,” before they can claim, on that ground, that they themselves have a right to control it; to seize, for their purposes, so much of every man’s property within it, as they may choose; and, at their discretion, to compel any man to risk his own life, or take the lives of other men, for the maintenance of their power.

To speak of either their numbers, or their strength, is not to the purpose. The question is by what right does the nation exist? And by what right are so many atrocities committed by its authority? or for its preservation?

The answer to this question must certainly be, that at least such a nation exists by no right whatever.

We are, therefore, driven to the acknowledgment that nations and governments, if they can rightfully exist at all, can exist only by consent. [*11]

IV.

The question, then, returns, what is implied in a government’s resting on consent?

Manifestly this one thing (to say nothing of the others) is necessarily implied in the idea of a government’s resting on consent, viz: the separate, individual consent of every man who is required to contribute, either by taxation or personal service, to the support of the government. All this, or nothing, is necessarily implied, because one man’s consent is just as necessary as any other man’s. If, for example, A claims that his consent is necessary to the establishment or maintenance of government, he thereby necessarily admits that B’s and every other man’s are equally necessary; because B’s and every other man’s right are just as good as his own. On the other hand, if he denies that B’s or any other particular man’s consent is necessary, he thereby necessarily admits that neither his own, nor any other man’s is necessary; and that government need to be founded on consent at all.

There is, therefore, no alternative but to say, either that the separate, individual consent of every man, who is required to aid, in any way, in supporting the government, is necessary, or that the consent of no one is necessary.

Clearly this individual consent is indispensable to the idea of treason; for if a man has never consented or agreed to support a government, he breaks no faith in refusing to support it. And if he makes war upon it, he does so as an open enemy, and not as a traitor that is, as a betrayer, or treacherous friend.

All this, or nothing, was necessarily implied in the Declaration made in 1776. If the necessity for consent, then announced, was a sound principle in favor of three millions of men, it was an equally sound one in favor of three men, or of one man. If the principle was a sound one in behalf of men living on a separate continent, it was an equally sound one in behalf of a man living on a separate farm, or in a separate house. [*12]

Moreover, it was only as separate individuals, each acting for himself, and not as members of organized governments, that the three millions declared their consent to be necessary to their support of a government; and, at the same time, declared their dissent to the support of the British Crown. The governments, then existing in the Colonies, had no constitutional power, as governments, to declare the separation between England and America. On the contrary, those governments, as governments, were organized under charters from, and acknowledged allegiance to, the British Crown. Of course the British king never made it one of the chartered or constitutional powers of those governments, as governments, to absolve the people from their allegiance to himself. So far, therefore, as the Colonial Legislatures acted as revolutionists, they acted only as so many individual revolutionists, and not as constitutional legislatures. And their representatives at Philadelphia, who first declared Independence, were, in the eye of the constitutional law of that day, simply a committee of Revolutionists, and in no sense constitutional authorities, or the representatives of constitutional authorities.

It was also, in the eye of the law, only as separate individuals, each acting for himself, and exercising simply his natural rights as an individual, that the people at large assented to, and ratified the Declaration.

It was also only as so many individuals, each acting for himself, and exercising simply his natural rights, that they revolutionized the constitutional character of their local governments, (so as to exclude the idea of allegiance to Great Britain); changing their forms only as and when their convenience dictated.

The whole Revolution, therefore, as a Revolution, was declared and accomplished by the people, acting separately as individuals, and exercising each his natural rights, and not by their governments in the exercise of their constitutional powers.

It was, therefore, as individuals, and only as individuals, each acting for himself alone, that they declared that their consent that is, their individual consent for each one could consent only [*13] for himself — was necessary to the creation or perpetuity of any government that they could rightfully be called on to support.

In the same way each declared, for himself, that his own will, pleasure, and discretion were the only authorities he had any occasion to consult, In determining whether he would any longer support the government under which be had always lived. And if this action of each individual were valid and rightful when he had so many other individuals to keep him company, it would have been, in the view of natural justice and right, equally valid and rightful, if he had taken the same step alone. He had the same natural right to take up arms alone to defend his own property against a single tax-gatherer, that he had to take up arms in company with three millions of others, to defend the property of all against an army of tax-gatherers.

Thus the whole Revolution turned upon, asserted, and, in theory, established, the right of each and every man, at his discretion, to release himself from the support of the government under which he had lived. And this principle was asserted, not as a right peculiar to themselves, or to that time, or as applicable only to the government then existing; but as a universal right of all men, at all times, and under all circumstances.

George the Third called our ancestors traitors for what they did at that time. But they were not traitors in fact, whatever he or his laws may have called them. They were not traitors in fact, because they betrayed nobody, and broke faith with nobody. They were his equals, owing him no allegiance, obedience, nor any other duty, except such as they owed to mankind at large. Their political relations with him had been purely voluntary. They had never pledged their faith to him that they would continue these relations any longer than it should please them to do so; and therefore they broke no faith in parting with him. They simply exercised their natural right of saying to him, and to the English people, that they were under no obligation to continue their political connexion with them, and that, for reasons of their own, they chose to dissolve it. [*14]

What was true of our ancestors, is true of revolutionists in general. The monarchs and governments, from whom they choose to separate, attempt to stigmatize them as traitors. But they are not traitors in fact; in-much they betray, and break faith with, no one. Having pledged no faith, they break none. They are simply men, who, for reasons of their own — whether good or bad, wise or unwise, is immaterial — choose to exercise their natural right of dissolving their connexion with the governments under which they have lived. In doing this, they no more commit the crime of treason — which necessarily implies treachery, deceit, breach of faith — than a man commits treason when he chooses to leave a church, or any other voluntary association, with which he has been connected.

This principle was a true one in 1776. It is a true one now. It is the only one on which any rightful government can rest. It is the one on which the Constitution itself professes to rest. If it does not really rest on that basis, it has no right to exist; and it is the duty of every man to raise his hand against it.

If the men of the Revolution designed to incorporate in the Constitution the absurd ideas of allegiance and treason, which they had once repudiated, against which they had fought, and by which the world had been enslaved, they thereby established for themselves an indisputable claim to the disgust and detestation of all mankind.

____________

In subsequent numbers, the author hopes to show that, under the principle of individual consent, the little government that mankind need, is not only practicable, but natural and easy; and that the Constitution of the United States authorizes no government, except one depending wholly on voluntary support.

NO TREASON.

No. II.

_____________

The Constitution.

_____________

BY LYSANDER SPOONER

_____________

BOSTON:

PUBLISHED BY THE AUTHOR,

No. 14 Bromfield Street.

1867.

___________________________________________________

Entered according to Act of congress, in the year 1867,

By LYSANDER SPOONER,

in the Clerk’s office of the District Court of the United States, for the District

of Massachusetts.

___________________________________________________

[*3]

NO TREASON.

NO. II

I.

The Constitution says:

“We, the people of the United States, in order to form a more perfect union, establish justice, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.”

The meaning of this is simply We, the people of the United States, acting freely and voluntarily as individuals, consent and agree that we will cooperate with each other in sustaining such a government as is provided for in this Constitution.

The necessity for the consent of “the people” is implied in this declaration. The whole authority of the Constitution rests upon it. If they did not consent, it was of no validity. Of course it had no validity, except as between those who actually consented. No one’s consent could be presumed against him, without his actual consent being given, any more than in the case of any other contract to pay money, or render service. And to make it binding upon any one, his signature, or other positive evidence of consent, was as necessary as in the case of any other-contract. If the instrument meant to say that any of “the people of the United States” would be bound by it, who [*4] did not consent, it was a usurpation and a lie. The most that can be inferred from the form, “We, the people,” is, that the instrument offered membership to all “the people of the United States;” leaving it for them to accept or refuse it, at their pleasure.

The agreement is a simple one, like any other agreement. It is the same as one that should say: We, the people of the town of A—–, agree to sustain a church, a school, a hospital, or a theatre, for ourselves and our children.

Such an agreement clearly could have no validity, except as between those who actually consented to it. If a portion only of “the people of the town of A—–,” should assent to this contract, and should then proceed to compel contributions of money or service from those who had not consented, they would be mere robbers; and would deserve to be treated as such.

Neither the conduct nor the rights of these signers would be improved at all by their saying to the dissenters: We offer you equal rights with ourselves, in the benefits of the church, school, hospital, or theatre, which we propose to establish, and equal voice in the control of it. It would be a sufficient answer for the others to say: We want no share in the benefits, and no voice in the control, of your institution; and will do nothing to support it.

The number who actually consented to the Constitution of the United States, at the first, was very small. Considered as the act of the whole people, the adoption of the Constitution was the merest farce and imposture, binding upon nobody.

The women, children, and blacks, of course, were not asked to give their consent. In addition to this, there were, in nearly or quite all the States, property qualifications that excluded probable one half, two thirds, or perhaps even three fourths, of the white male adults from the right of suffrage. And of those who were allowed that right, we know not how many exercised it.

Furthermore, those who originally agreed to the Constitution, could thereby bind nobody that should come after them. They could contract for nobody but themselves. They had no more [*5] natural right or power to make political contracts, binding upon succeeding generations, than they had to make marriage or business contracts binding upon them.

Still further. Even those who actually voted for the adoption of the Constitution, did not pledge their faith for any specific time; since no specific time was named, in the Constitution, during which the association should continue. It was, therefore, merely an association during pleasure; even as between the original parties to it. Still less, if possible, has it been any thing more than a merely voluntary association, during pleasure, between the succeeding generations, who have never gone through, as their fathers did, with so much even as any outward formality of adopting it, or of pledging their faith to support it. Such portions of them as pleased, and as the States permitted to vote, have only done enough, by voting and paying taxes, (and unlawfully and tyrannically extorting taxes from others,) to keep the government in operation for the time being. And this, in the view of the Constitution, they have done voluntarily, and because it was for their interest, or pleasure, and not because they were under any pledge or obligation to do it. Any one man, or any number of men, have had a perfect right, at any time, to refuse his or their further support; and nobody could rightfully object to his or their withdrawal.

There is no escape from these conclusions, if we say that the adoption of the Constitution was the act of the people, as individuals, and not of the States, as States. On the other hand, if we say that the adoption was the act of the States, as States, it necessarily follows that they had the right to secede at pleasure, inasmuch as they engaged for no specific time.

The consent, therefore, that has been given, whether by individuals, or by the States, has been, at most, only a consent for the time being; not an engagement for the future. In truth, in the case of individuals, their actual voting is not to be taken as proof of consent, even for the time being. On the contrary, it is to be considered that, without his consent having ever been asked, a [*6] man finds himself environed by a government that he cannot resist; a government that forces him to pay money, render service, and forego the exercise of many of his natural rights, under peril of weighty punishments. He sees, too, that other men practise this tyranny over him by the use of the ballot. He sees further that, if he will but use the ballot himself, he has some chance of relieving himself from this tyranny of others, by subjecting them to his own. In short, be finds himself, without his consent, so situated that, if he use the ballot, he may become a master; if he does not use it, he must become a slave. And he has no other alternative than these two. In self-defence, he attempts the former. His case is analogous to that of a man who has been forced into battle, where he must either kill others, or be killed himself. Because, to save his own life in battle, a man attempts to take the lives of his opponents, it is not to be inferred that the battle is one of his own choosing. Neither in contests with the ballot — which is a mere substitute for a bullet — because, as his only chance of self-preservation, a man uses a ballot, is it to be inferred that the contest is one into which he voluntarily entered; that he voluntarily set up all his own natural rights, as a stake against those of others, to be lost or won by the mere power of numbers. On the contrary, it is to be considered that, in an exigency, into which he had been forced by others, and in which no other means of self-defence offered, he, as a matter of necessity, used the only one that was left to him.

Doubtless the most miserable of men, under the most oppressive government in the world, if allowed the ballot, would use it, if they could see any chance of thereby ameliorating their condition. But it would not therefore be a legitimate inference that the government itself, that crushes them, was one which they had voluntarily set up, or ever consented to.

Therefore a man’s voting under the Constitution of the United States, is not to be taken as evidence that he ever freely assented to the Constitution, even for the time being. Consequently we have no proof that any very large portion, even of the actual [*7] voters of the United States, ever really and voluntarily consented to the Constitution, even for the time being. Nor can we ever have such proof, until every man is left perfectly free to consent, or not, without thereby subjecting himself or his property to injury or trespass from others.

II.

The Constitution says:

“Treason against the United States shall consist only in levying war against them, or in adhering to their enemies, giving them aid and comfort.”

This is the only definition of treason given by the Constitution, and it is to be interpreted, like all other criminal laws, in the sense most favorable to liberty and justice. Consequently the treason here spoken of, must be held to be treason in fact, and not merely something that may have been falsely called by that name.

To determine, then, what is treason in fact, we are not to look to the codes of Kings, and Czars, and Kaisers, who maintain their power by force and fraud; who contemptuously call mankind their “subjects;” who claim to have a special license from heaven to rule on earth; who teach that it is a religious duty of mankind to obey them; who bribe a servile and corrupt priest-hood to impress these ideas upon the ignorant and superstitious; who spurn the idea that their authority is derived from, or dependent at all upon, the consent of their people; and who attempt to defame, by the false epithet of traitors, all who assert their own rights, and the rights of their fellow men, against such usurpations.

Instead of regarding this false and calumnious meaning of the word treason, we are to look at its true and legitimate meaning in our mother tongue; at its use in common life; and at what would necessarily be its true meaning in any other contracts, or articles [*8] of association, which men might voluntarily enter into with each other.

The true and legitimate meaning of the word treason, then, necessarily implies treachery, deceit, breach of faith. Without these, there can be no treason. A traitor is a betrayer — one who practices injury, while professing friendship. Benedict Arnold was a traitor, solely because, while professing friendship for the American cause, he attempted to injure it. An open enemy, however criminal in other respects, is no traitor.

Neither does a man, who has once been my friend, become a traitor by becoming an enemy, if before doing me an injury, he gives me fair warning that he has become an enemy; and if he makes no unfair use of any advantage which my confidence, in the time of our friendship, had placed in his power.

For example, our fathers — even if we were to admit them to have been wrong in other respects — certainly were not traitors in fact, after the fourth of July, 1776; since on that day they gave notice to the King of Great Britain that they repudiated his authority, and should wage war against him. And they made no unfair use of any advantages which his confidence had previously placed in their power.

It cannot be denied that, in the late war, the Southern people proved themselves to be open and avowed enemies, and not treacherous friends. It cannot be denied that they gave us fair warning that they would no longer be our political associates, but would, if need were, fight for a separation. It cannot be alleged that they made any unfair use of advantages which our confidence, in the time of our friendship, had placed in their power. Therefore they were not traitors in fact: and consequently not traitors within the meaning of the Constitution.

Furthermore, men are not traitors in fact, who take up arms against the government, without having disavowed allegiance to it, provided they do it, either to resist the usurpations of the government, or to resist what they sincerely believe to be such usurpations. [*9]

It is a maxim of law that there can be no crime without a criminal intent. And this maxim is as applicable to treason as to any other crime. For example, our fathers were not traitors in fact, for resisting the British Crown, before the fourth of July, 1776 — that is, before they had thrown off allegiance to him — provided they honestly believed that they were simply defending their rights against his usurpations. Even if they were mistaken in their law, that mistake, if an innocent one, could not make them traitors in fact.

For the same reason, the Southern people, if they sincerely believed — as it has been extensively, if not generally, conceded, at the North, that they did — in the so-called constitutional theory of “State Rights,” did not become traitors in fact, by acting upon it; and consequently not traitors within the meaning of the Constitution.

III.

The Constitution does not say who will become traitors, by “levying war against the United States, or adhering to their enemies, giving them aid and comfort.”

It is, therefore, only by inference, or reasoning, that we can know who will become traitors by these acts.

Certainly if Englishmen, Frenchmen, Austrians, or Italians, making no professions of support or friendship to the United States, levy war against them, or adhere to their enemies, giving them aid and comfort, they do not thereby make themselves traitors, within the meaning of the Constitution; and why? Solely because they would not be traitors in fact. Making no professions of support or friendship, they would practice no treachery, deceit, or breach of faith. But if they should voluntarily enter either the civil or military service of the United States, and pledge fidelity to them, (without being naturalized,) and should then betray the trusts reposed in them, either by turning their guns against the United States, or by giving aid [*10] and comfort to their enemies, they would be traitors in fact; and therefore traitors within the meaning of the Constitution; and could be lawfully punished as such.

There is not, in the Constitution, a syllable that implies that persons, born within the territorial limits of the United States, have allegiance imposed upon them on account of their birth in the country, or that they will be judged by any different rule, on the subject of treason, than persons of foreign birth. And there is no power, in Congress, to add to, or alter, the language of the Constitution, on this point, so as to make it more comprehensive than it now is. Therefore treason in fact — that is, actual treachery, deceit, or breach of faith — must be shown in the case of a native of the United States, equally as in the case of a foreigner, before he can be said to be a traitor.

Congress have seen that the language of the Constitution was insufficient, of itself to make a man a traitor — on the ground of birth in this country — who levies war against the United States, but practices no treachery, deceit, or breach of faith. They have, therefore — although they had no constitutional power to do so — apparently attempted to enlarge the language of the Constitution on this point. And they have enacted:

“That if any person or persons, owing allegiance to the United States of America, shall levy war against them, or shall adhere to their enemies, giving them aid and comfort, * * * such person or persons shall be adjudged guilty of treason against the United States, and shall suffer death.” — Statute, April 30, 1790, Section 1.

It would be a sufficient answer to this enactment to say that it is utterly unconstitutional, if its effect would be to make any man a traitor, who would not have been one under the language of the Constitution alone.

The whole pith of the act lies in the words, “persons owing allegiance to the United States.” But this language really leaves the question where it was before, for it does not attempt to [*11] show or declare who does “owe allegiance to the United States;” although those who passed the act, no doubt thought, or wished others to think, that allegiance was to be presumed (as is done under other governments) against all born in this country, (unless possibly slaves).

The Constitution itself, uses no such word as “allegiance,” “sovereignty,” “loyalty,” “subject,” or any other term, such as is used by other governments, to signify the services, fidelity, obedience, or other duty, which the people are assumed to owe to their government, regardless of their own will in the matter. As the Constitution professes to rest wholly on consent, no one can owe allegiance, service, obedience, or any other duty to it, or to the government created by it, except with his own consent.

The word allegiance comes from the Latin words ad and ligo, signifying to bind to. Thus a man under allegiance to a government, is a man bound to it; or bound to yield it support and fidelity. And governments, founded otherwise than on consent, hold that all persons born under them, are under allegiance to them; that is, are bound to render them support, fidelity, and obedience; and are traitors if they resist them.

But it is obvious that, in truth and in fact, no one but himself can bind any one to support any government. And our Constitution admits this fact when it concedes that it derives its authority wholly from the consent of the people. And the word treason is to be understood in accordance with that idea.

It is conceded that a person of foreign birth comes under allegiance to our government only by special voluntary contract. If a native has allegiance imposed upon him, against his will, he is in a worse condition than the foreigner; for the latter can do as he pleases about assuming that obligation. The accepted interpretation of the Constitution, therefore, makes the foreigner a free person, on this point, while it makes the native a slave.

The only difference — if there be any — between natives and foreigners, in respect of allegiance, is, that a native has a right — offered to him by the Constitution — to come under allegiance to [*12] the government, if be so please; and thus. entitle himself to membership in the body politic. His allegiance cannot be refused. Whereas a foreigner’s allegiance can be refused, if the government so please.

IV.

The Constitution certainly supposes that the crime of treason can be committed only by man, as an individual. It would be very curious to see a man indicted, convicted, or hanged, otherwise than as an individual; or accused of having committed his treason otherwise than as an individual. And yet it is clearly impossible that any one can be personally guilty of treason, can be a traitor in fact, unless he, as an individual, has in some way voluntarily pledged his faith and fidelity to the government. Certainly no man, or body of men, could pledge it for him, without his consent; and no man, or body of men, have any right to presume it against him, when he has not pledged it, himself.

V.

It is plain, therefore, that if, when the Constitution says treason, it means treason — treason in fact, and nothing else — there is no ground at all for pretending that the Southern people have committed that crime. But if, on the other hand, when the Constitution says treason, it means what the Czar and the Kaiser mean by treason, then our government is, in principle, no better than theirs; and has no claim whatever to be considered a free government.

VI.

One essential of a free government is that it rest wholly on voluntary support. And one certain proof that a government is not free, is that it coerces more or less persons to support it, against their will. All governments, the worst on earth, and the [*13] most tyrannical on earth, are free governments to that portion of the people who voluntarily support them. And all governments though the best on earth in other respects — are nevertheless tyrannies to that portion of the people — whether few or many — who are compelled to support them against their will. A government is like a church, or any other institution, in these respects. There is no other criterion whatever, by which to determine whether a government is a free one, or not, than the single one of its depending, or not depending, solely on voluntary support.

VII.

No middle ground is possible on this subject. Either “taxation without consent is robbery,” or it is not. If it is not, then any number of men, who choose, may at any time associate; call themselves a government; assume absolute authority over all weaker than themselves; plunder them at will; and kill them if they resist. If, on the other hand, taxation without consent is robbery, it necessarily follows that every man who has not consented to be taxed, has the same natural right to defend his property against a taxgatherer, that he has to defend it against a highwayman.

VIII.

It is perhaps unnecessary to say that the principles of this argument are as applicable to the State governments, as to the national one.

The opinions of the South, on the subjects of allegiance and treason, have been equally erroneous with those of the North. The only difference between them, has been, that the South has had that a man was (primarily) under involuntary allegiance to the State government; while the North held that he was (primarily) under a similar allegiance to the United States government; whereas, in truth, he was under no involuntary allegiance to either. [*14]

IX.

Obviously there can be no law of treason more stringent than has now been stated, consistently with political liberty. In the very nature of things there can never be any liberty for the weaker party, on any other principle; and political liberty always means liberty for the weaker party. It is only the weaker party that is ever oppressed. The strong are always free by virtue of their superior strength. So long as government is a mere contest as to which of two parties shall rule the other, the weaker must always succumb. And whether the contest be carried on with ballots or bullets, the principle is the same; for under the theory of government now prevailing, the ballot either signifies a bullet, or it signifies nothing. And no one can consistently use a ballot, unless he intends to use a bullet, if the latter should be needed to insure submission to the former.

X.

The practical difficulty with our government has been, that most of those who have administered it, have taken it for granted that the Constitution, as it is written, was a thing of no importance; that it neither said what it meant, nor meant what it said; that it was gotten up by swindlers, (as many of its authors doubtless were,) who said a great many good things, which they did not mean, and meant a great many bad things, which they dared not say; that these men, under the false pretence of a government resting on the consent of the whole people, designed to entrap them into a government of a part; who should be powerful and fraudulent enough to cheat the weaker portion out of all the good things that were said, but not meant, and subject them to all the bad things that were meant, but not said. And most of those who have administered the government, have assumed that all these swindling intentions were to be carried into effect, in the place of the written Constitution. Of all these swindles, the [*15] treason swindle is the most flagitious. It is the most flagitious, because it is equally flagitious, in principle, with any; and it includes all the others. It is the instrumentality by which all the others are mode effective. A government that can at pleasure accuse, shoot, and hang men, as traitors, for the one general offence of refusing to surrender themselves and their property unreservedly to its arbitrary will, can practice any and all special and particular oppressions it pleases.

The result — and a natural one — has been that we have had governments, State and national, devoted to nearly every grade and species of crime that governments have ever practised upon their victims; and these crimes have culminated in a war that has cost a million of lives; a war carried on, upon one side, for chattel slavery, and on the other for political slavery; upon neither for liberty, justice, or truth. And these crimes have been committed, and this war waged, y men, and the descendants of men, who, less than a hundred years ago, said that all men were equal, and could owe neither service to individuals, nor allegiance to governments, except with their own consent.

XI.

No attempt or pretence, that was ever carried into practical operation amongst civilized men — unless possibly the pretence of a “Divine Right,” on the part of some, to govern and enslave others embodied so much of shameless absurdity, falsehood, impudence, robbery, usurpation, tyranny, and villany of every kind, as the attempt or pretence of establishing a government by consent, and getting the actual consent of only so many as may be necessary to keep the rest in subjection by force. Such a government is a mere conspiracy of the strong against the weak. It no more rests on consent than does the worst government on earth.

What substitute for their consent is offered to the weaker party, whose rights are thus annihilated, struck out of existence, [*16] by the stronger? Only this: Their consent is presumed! That is, these usurpers condescendingly and graciously presume that those whom they enslave, consent to surrender their all of life, liberty, and property into the hands of those who thus usurp dominion over them! And it is pretended that this presumption of their consent — when no actual consent has been given — is sufficient to save the rights of the victims, and to justify the usurpers! As well might the highwayman pretend to justify himself by presuming that the traveller consents to part with his money. As well might the assassin justify himself by simply presuming that his victim consents to part with his life. As well the holder of chattel slaves to himself by presuming that they consent to his authority, and to the whips and the robbery which he practises upon them. The presumption is simply a presumption that the weaker party consent to be slaves.

Such is the presumption on which alone our government relies to justify the power it maintains over its unwilling subjects. And it was to establish that presumption as the inexorable and perpetual law of this country, that so much money and blood have been expended.

NO TREASON.

No. VI.

_____________

The Constitution of no Authority.

_____________

BY LYSANDER SPOONER

_____________

BOSTON:

PUBLISHED BY THE AUTHOR,

1870.

___________________________________________________

Entered according to Act of congress, in the year 1870,

By LYSANDER SPOONER,

in the Clerk’s office of the District Court of the United States, for the District

of Massachusetts.

___________________________________________________

The first and second numbers of this series were published in 1867. For reasons not necessary to be explained, the sixth is now published in advance of the third, fourth, and fifth.

[*3]

NO TREASON

NO. VI.

THE CONSTITUTION OF NO AUTHORITY

I.

The Constitution has no inherent authority or obligation. It has no authority or obligation at all, unless as a contract between man and man. And it does not so much as even purport to be a contract between persons now existing. It purports, at most, to be only a contract between persons living eighty years ago. And it can be supposed to have been a contract then only between persons who had already come to years of discretion, so as to be competent to make reasonable and obligatory contracts. Furthermore, we know, historically, that only a small portion even of the people then existing were consulted on the subject, or asked, or permitted to express either their consent or dissent in any formal manner. Those persons, if any, who did give their consent formally, are all dead now. Most of them have been dead forty, fifty, sixty, or seventy years. And the constitution, so far as it was their contract, died with them. They had no natural power or right to make it obligatory upon their children. It is not only plainly impossible, in the nature of things, that they could bind their posterity, but they did not even attempt to bind them. That is to say, the instrument does not purport to be an agreement between any body but “the people” then existing; nor does it, either ex- [*4] pressly or impliedly, assert any right, power, or disposition, on their part, to bind anybody but themselves. Let us see. Its language is:

“We, the people of the United States (that is, the people then existing in the United States), in order to form a more perfect union, insure domestic tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general welfare, and secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.”

It is plain, in the first place, that this language, as an agreement, purports to be only what it at most really was, viz., a contract between the people then existing; and, of necessity, binding, as a contract, only upon those then existing. In the second place, the language neither expresses nor implies that they had any right or power, to bind their “posterity” to live under it. It does not say that their “posterity” will, shall, or must live under it. It only says, in effect, that their hopes and motives in adopting it were that it might prove useful to their posterity, as well as to themselves, by promoting their union, safety, tranquility, liberty, etc.

Suppose an agreement were entered into, in this form:

We, the people of Boston, agree to maintain a fort on Governor’s Island, to protect ourselves and our posterity against invasion.

This agreement, as an agreement, would clearly bind nobody but the people then existing. Secondly, it would assert no right, power, or disposition, on their part, to compel, their “posterity” to maintain such a fort. It would only indicate that the supposed welfare of their posterity was one of the motives that induced the original parties to enter into the agreement.

When a man says he is building a house for himself and his posterity, he does not mean to be understood as saying that he has any thought of binding them, nor is it to be inferred that he [*5] is so foolish as to imagine that he has any right or power to bind them, to live in it. So far as they are concerned, he only means to be understood as saying that his hopes and motives, in building it, are that they, or at least some of them, may find it for their happiness to live in it.

So when a man says he is planting a tree for himself and his posterity, he does not mean to be understood as saying that he has any thought of compelling them, nor is it to be inferred that he is such a simpleton as to imagine that he has any right or power to compel them, to eat the fruit. So far as they are concerned, he only means to say that his hopes and motives, in planting the tree, are that its fruit may be agreeable to them.

So it was with those who originally adopted the Constitution. Whatever may have been their personal intentions, the legal meaning of their language, so far as their “posterity” was concerned, simply was, that their hopes and motives, in entering into the agreement, were that it might prove useful and acceptable to their posterity; that it might promote their union, safety, tranquility, and welfare; and that it might tend “to secure to them the blessings of liberty.” The language does not assert nor at all imply, any right, power, or disposition, on the part of the original parties to the agreement, to compel their “posterity” to live under it. If they had intended to bind their posterity to live under it, they should have said that their objective was, not “to secure to them the blessings of liberty,” but to make slaves of them; for if their “posterity” are bound to live under it, they are nothing less than the slaves of their foolish, tyrannical, and dead grandfathers.

It cannot be said that the Constitution formed “the people of the United States,” for all time, into a corporation. It does not speak of “the people” as a corporation, but as individuals. A corporation does not describe itself as “we,” nor as “people,” nor as “ourselves.” Nor does a corporation, in legal language, [*6] have any “posterity.” It supposes itself to have, and speaks of itself as having, perpetual existence, as a single individuality.

Moreover, no body of men, existing at any one time, have the power to create a perpetual corporation. A corporation can become practically perpetual only by the voluntary accession of new members, as the old ones die off. But for this voluntary accession of new members, the corporation necessarily dies with the death of those who originally composed it.

Legally speaking, therefore, there is, in the Constitution, nothing that professes or attempts to bind the “posterity” of those who establish[ed] it.

If, then, those who established the Constitution, had no power to bind, and did not attempt to bind, their posterity, the question arises, whether their posterity have bound themselves. If they have done so, they can have done so in only one or both of these two ways, viz., by voting, and paying taxes.

II.

Let us consider these two matters, voting and tax paying, separately. And first of voting.

All the voting that has ever taken place under the Constitution, has been of such a kind that it not only did not pledge the whole people to support the Constitution, but it did not even pledge any one of them to do so, as the following considerations show.

1. In the very nature of things, the act of voting could bind nobody but the actual voters. But owing to the property qualifications required, it is probable that, during the first twenty or thirty years under the Constitution, not more than one-tenth, fifteenth, or perhaps twentieth of the whole population (black and white, men, women, and minors) were permitted to vote. Consequently, so far as voting was concerned, not more than one-tenth, fifteenth, or twentieth of those then existing, could have incurred any obligation to support the Constitution. [*7]

At the present time, it is probable that not more than one-sixth of the whole population are permitted to vote. Consequently, so far as voting is concerned, the other five-sixths can have given no pledge that they will support the Constitution.

2. Of the one-sixth that are permitted to vote, probably not more than two-thirds (about one-ninth of the whole population) have usually voted. Many never vote at all. Many vote only once in two, three, five, or ten years, in periods of great excitement.

No one, by voting, can be said to pledge himself for any longer period than that for which he votes. If, for example, I vote for an officer who is to hold his office for only a year, I cannot be said to have thereby pledged myself to support the government beyond that term. Therefore, on the ground of actual voting, it probably cannot be said that more than one-ninth or one-eighth, of the whole population are usually under any pledge to support the Constitution.

3. It cannot be said that, by voting, a man pledges himself to support the Constitution, unless the act of voting be a perfectly voluntary one on his part. Yet the act of voting cannot properly be called a voluntary one on the part of any very large number of those who do vote. It is rather a measure of necessity imposed upon them by others, than one of their own choice. On this point I repeat what was said in a former number, <fn1> viz.:

“In truth, in the case of individuals, their actual voting is not to be taken as proof of consent, even for the time being. On the contrary, it is to be considered that, without his consent having even been asked a man finds himself environed by a government that he cannot resist; a government that forces him to pay money, render service, and forego the exercise of many of his natural rights, under peril of weighty punishments. He sees, too, that other men practice this tyranny over him by the use of the ballot. He sees further, that, if he will but use the ballot [*8] himself, he has some chance of relieving himself from this tyranny of others, by subjecting them to his own. In short, he finds himself, without his consent, so situated that, if he use the ballot, he may become a master; if he does not use it, he must become a slave. And he has no other alternative than these two. In self-defence, he attempts the former. His case is analogous to that of a man who has been forced into battle, where he must either kill others, or be killed himself. Because, to save his own life in battle, a man takes the lives of his opponents, it is not to be inferred that the battle is one of his own choosing. Neither in contests with the ballot — which is a mere substitute for a bullet — because, as his only chance of self- preservation, a man uses a ballot, is it to be inferred that the contest is one into which he voluntarily entered; that he voluntarily set up all his own natural rights, as a stake against those of others, to be lost or won by the mere power of numbers. On the contrary, it is to be considered that, in an exigency into which he had been forced by others, and in which no other means of self-defence offered, he, as a matter of necessity, used the only one that was left to him.

“Doubtless the most miserable of men, under the most oppressive government in the world, if allowed the ballot, would use it, if they could see any chance of thereby meliorating their condition. But it would not, therefore, be a legitimate inference that the government itself, that crushes them, was one which they had voluntarily set up, or even consented to. “Therefore, a man’s voting under the Constitution of the United States, is not to be taken as evidence that he ever freely assented to the Constitution, even for the time being. Consequently we have no proof that any very large portion, even of the actual voters of the United States, ever really and voluntarily consented to the Constitution, even for the time being. Nor can we ever have such proof, until every man is left perfectly free to consent, or not, without thereby subjecting himself or his property to be disturbed or injured by others.”

As we can have no legal knowledge as to who votes from choice, and who from the necessity thus forced upon him, we can have no legal knowledge, as to any particular individual, that he voted from choice; or, consequently, that by voting, he consented, or pledged himself, to support the government. Legally [*9] speaking, therefore, the act of voting utterly fails to pledge any one to support the government. It utterly fails to prove that the government rests upon the voluntary support of anybody. On general principles of law and reason, it cannot be said that the government has any voluntary supporters at all, until it can be distinctly shown who its voluntary supporters are.

4. As taxation is made compulsory on all, whether they vote or not, a large proportion of those who vote, no doubt do so to prevent their own money being used against themselves; when, in fact, they would have gladly abstained from voting, if they could thereby have saved themselves from taxation alone, to say nothing of being saved from all the other usurpations and tyrannies of the government. To take a man’s property without his consent, and then to infer his consent because he attempts, by voting, to prevent that property from being used to his injury, is a very insufficient proof of his consent to support the Constitution. It is, in fact, no proof at all. And as we can have no legal knowledge as to who the particular individuals are, if there are any, who are willing to be taxed for the sake of voting, we can have no legal knowledge that any particular individual consents to be taxed for the sake of voting; or, consequently, consents to support the Constitution.

5. At nearly all elections, votes are given for various candidates for the same office. Those who vote for the unsuccessful candidates cannot properly be said to have voted to sustain the Constitution. They may, with more reason, be supposed to have voted, not to support the Constitution, but specially to prevent the tyranny which they anticipate the successful candidate intends to practice upon them under color of the Constitution; and therefore may reasonably be supposed to have voted against the Constitution itself. This supposition is the more reasonable, inasmuch as such voting is the only mode allowed to them of expressing their dissent to the Constitution. [*10]

6. Many votes are usually given for candidates who have no prospect of success. Those who give such votes may reasonably be supposed to have voted as they did, with a special intention, not to support, but to obstruct the execution of, the Constitution; and, therefore, against the Constitution itself.

7. As all the different votes are given secretly (by secret ballot), there is no legal means of knowing, from the votes themselves, who votes for, and who votes against, the Constitution. Therefore, voting affords no legal evidence that any particular individual supports the Constitution. And where there can be no legal evidence that any particular individual supports the Constitution, it cannot legally be said that anybody supports it. It is clearly impossible to have any legal proof of the intentions of large numbers of men, where there can be no legal proof of the intentions of any particular one of them.

8. There being no legal proof of any man’s intentions, in voting, we can only conjecture them. As a conjecture, it is probable, that a very large proportion of those who vote, do so on this principle, viz., that if, by voting, they could but get the government into their own hands (or that of their friends), and use its powers against their opponents, they would then willingly support the Constitution; but if their opponents are to have the power, and use it against them, then they would not willingly support the Constitution.

In short, men’s voluntary support of the Constitution is doubtless, in most cases, wholly contingent upon the question whether, by means of the Constitution, they can make themselves masters, or are to be made slaves.

Such contingent consent as that is, in law and reason, no consent at all.

9. As everybody who supports the Constitution by voting (if there are any such) does so secretly (by secret ballot), and in a way to avoid all personal responsibility for the acts of his agents or representatives, it cannot legally or reasonably be [*11] said that anybody at all supports the Constitution by voting. No man can reasonably or legally be said to do such a thing as assent to, or support, the Constitution, unless he does it openly, and in a way to make himself personally responsible for the acts of his agents, so long as they act within the limits of the power he delegates to them.

10. As all voting is secret (by secret ballot), and as all secret governments are necessarily only secret bands of robbers, tyrants, and murderers, the general fact that our government is practically carried on by means of such voting, only proves that there is among us a secret band of robbers, tyrants, and murderers, whose purpose is to rob, enslave, and, so far as necessary to accomplish their purposes, murder, the rest of the people. The simple fact of the existence of such a band does nothing towards proving that “the people of the United States,” or any one of them, voluntarily supports the Constitution.

For all the reasons that have now been given, voting furnishes no legal evidence as to who the particular individuals are (if there are any), who voluntarily support the Constitution. It therefore furnishes no legal evidence that anybody supports it voluntarily.

So far, therefore, as voting is concerned, the Constitution, legally speaking, has no supporters at all.

And, as a matter of fact, there is not the slightest probability that the Constitution has a single bona fide supporter in the country. That is to say, there is not the slightest probability that there is a single man in the country, who both understands what the Constitution really is, and sincerely supports it for what it really is.

The ostensible supporters of the Constitution, like the ostensible supporters of most other governments, are made up of three classes, viz.: 1. Knaves, a numerous and active class, who see in the government an instrument which they can use for their own aggrandizement or wealth. 2. Dupes — a large class, no [*12] doubt — each of whom, because he is allowed one voice out of millions in deciding what he may do with his own person and his own property, and because he is permitted to have the same voice in robbing, enslaving, and murdering others, that others have in robbing, enslaving, and murdering himself, is stupid enough to imagine that he is a “free man,” a “sovereign”; that this is “a free government”; “a government of equal rights,” “the best government on earth,” <fn2> and such like absurdities. 3. A class who have some appreciation of the evils of government, but either do not see how to get rid of them, or do not choose to so far sacrifice their private interests as to give themselves seriously and earnestly to the work of making a change.

III.

The payment of taxes, being compulsory, of course furnishes no evidence that any one voluntarily supports the Constitution.

1. It is true that the theory of our Constitution is, that all taxes are paid voluntarily; that our government is a mutual insurance company, voluntarily entered into by the people with each other; that that each man makes a free and purely voluntary contract with all others who are parties to the Constitution, to pay so much money for so much protection, the same as he does with any other insurance company; and that he is just as free not to be protected, and not to pay tax, as he is to pay a tax, and be protected.

But this theory of our government is wholly different from the practical fact. The fact is that the government, like a highwayman, says to a man: Your money, or your life.” And many, if not most, taxes are paid under the compulsion of that threat.

The government does not, indeed, waylay a man in a lonely place, spring upon him from the roadside, and, holding a pistol [*13] to his head, proceed to rifle his pockets. But the robbery is none the less a robbery on that account; and it is far more dastardly and shameful.

The highwayman takes solely upon himself the responsibility, danger, and crime of his own act. He does not pretend that he has any rightful claim to your money, or that he intends to use it for your own benefit. He does not pretend to be anything but a robber. He has not acquired impudence enough to profess to be merely a “protector,” and that he takes men’s money against their will, merely to enable him to “protect” those infatuated travellers, who feel perfectly able to protect themselves, or do not appreciate his peculiar system of protection. He is too sensible a man to make such professions as these. Furthermore, having taken your money, he leaves you, as you wish him to do. He does not persist in following you on the road, against your will; assuming to be your rightful “sovereign,” on account of the “protection” he affords you. He does not keep “protecting” you, by commanding you to bow down and serve him; by requiring you to do this, and forbidding you to do that; by robbing you of more money as often as he finds it for his interest or pleasure to do so; and by branding you as a rebel, a traitor, and an enemy to your country, and shooting you down without mercy, if you dispute his authority, or resist his demands. He is too much of a gentleman to be guilty of such impostures, and insults, and villanies as these. In short, he does not, in addition to robbing you, attempt to make you either his dupe or his slave.

The proceedings of those robbers and murderers, who call themselves “the government,” are directly the opposite of these of the single highwayman.

In the first place, they do not, like him, make themselves individually known; or, consequently, take upon themselves personally the responsibility of their acts. On the contrary, they secretly (by secret ballot) designate some one of their number [*14] to commit the robbery in their behalf, while they keep themselves practically concealed. They say to the person thus designated:

Go to A_____ B_____, and say to him that “the government” has need of money to meet the expenses of protecting him and his property. If he presumes to say that he has never contracted with us to protect him, and that he wants none of our protection, say to him that that is our business, and not his; that we choose to protect him, whether he desires us to do so or not; and that we demand pay, too, for protecting him. If he dares to inquire who the individuals are, who have thus taken upon themselves the title of “the government,” and who assume to protect him, and demand payment of him, without his having ever made any contract with them, say to him that that, too, is our business, and not his; that we do not choose to make ourselves individually known to him; that we have secretly (by secret ballot) appointed you our agent to give him notice of our demands, and, if he complies with them, to give him, in our name, a receipt that will protect him against any similar demand for the present year. If he refuses to comply, seize and sell enough of his property to pay not only our demands, but all your own expenses and trouble beside. If he resists the seizure of his property, call upon the bystanders to help you (doubtless some of them will prove to be members of our band.) If, in defending his property, he should kill any of our band who are assisting you, capture him at all hazards; charge him (in one of our courts) with murder; convict him, and hang him. If he should call upon his neighbors, or any others who, like him, may be disposed to resist our demands, and they should come in large numbers to his assistance, cry out that they are all rebels and traitors; that “our country” is in danger; call upon the commander of our hired murderers; tell him to quell the rebellion and “save the country,” cost what it may. Tell him to kill all who resist, though they should be hundreds of thou- [*15] sands; and thus strike terror into all others similarly disposed. See that the work of murder is thoroughly done; that we may have no further trouble of this kind hereafter. When these traitors shall have thus been taught our strength and our determination, they will be good loyal citizens for many years, and pay their taxes without a why or a wherefore.

It is under such compulsion as this that taxes, so called, are paid. And how much proof the payment of taxes affords, that the people consent to “support the government,” it needs no further argument to show.

2. Still another reason why the payment of taxes implies no consent, or pledge, to support the government, is that the taxpayer does not know, and has no means of knowing, who the particular individuals are who compose “the government.” To him “the government” is a myth, an abstraction, an incorporeality, with which he can make no contract, and to which he can give no consent, and make no pledge. He knows it only through its pretended agents. “The government” itself he never sees. He knows indeed, by common report, that certain persons, of a certain age, are permitted to vote; and thus to make themselves parts of, or (if they choose) opponents of, the government, for the time being. But who of them do thus vote, and especially how each one votes (whether so as to aid or oppose the government), he does not know; the voting being all done secretly (by secret ballot). Who, therefore, practically compose “the government,” for the time being, he has no means of knowing. Of course he can make no contract with them, give them no consent, and make them no pledge. Of necessity, therefore, his paying taxes to them implies, on his part, no contract, consent, or pledge to support them — that is, to support “the government,” or the Constitution.

3. Not knowing who the particular individuals are, who call themselves “the government,” the taxpayer does not know whom he pays his taxes to. All he knows is that a man comes to [*16] him, representing himself to be the agent of “the government” — that is, the agent of a secret band of robbers and murderers, who have taken to themselves the title of “the government,” and have determined to kill everybody who refuses to give them whatever money they demand. To save his life, he gives up his money to this agent. But as this agent does not make his principals individually known to the taxpayer, the latter, after he has given up his money, knows no more who are “the government” — that is, who were the robbers — than he did before. To say, therefore, that by giving up his money to their agent, he entered into a voluntary contract with them, that he pledges himself to obey them, to support them, and to give them whatever money they should demand of him in the future, is simply ridiculous.

4. All political power, so called, rests practically upon this matter of money. Any number of scoundrels, having money enough to start with, can establish themselves as a “government”; because, with money, they can hire soldiers, and with soldiers extort more money; and also compel general obedience to their will. It is with government, as Caesar said it was in war, that money and soldiers mutually supported each other; that with money he could hire soldiers, and with soldiers extort money. So these villains, who call themselves governments, well understand that their power rests primarily upon money. With money they can hire soldiers, and with soldiers extort money. And, when their authority is denied, the first use they always make of money, is to hire soldiers to kill or subdue all who refuse them more money.

For this reason, whoever desires liberty, should understand these vital facts, viz.: 1. That every man who puts money into the hands of a “government” (so called), puts into its hands a sword which will be used against him, to extort more money from him, and also to keep him in subjection to its arbitrary will. 2. That those who will take his money, without his con- [*17] sent, in the first place, will use it for his further robbery and enslavement, if he presumes to resist their demands in the future. 3. That it is a perfect absurdity to suppose that any body of men would ever take a man’s money without his consent, for any such object as they profess to take it for, viz., that of protecting him; for why should they wish to protect him, if he does not wish them to do so? To suppose that they would do so, is just as absurd as it would be to suppose that they would take his money without his consent, for the purpose of buying food or clothing for him, when he did not want it. 4. If a man wants “protection,” he is competent to make his own bargains for it; and nobody has any occasion to rob him, in order to “protect” him against his will. 5. That the only security men can have for their political liberty, consists in their keeping their money in their own pockets, until they have assurances, perfectly satisfactory to themselves, that it will be used as they wish it to be used, for their benefit, and not for their injury. 6. That no government, so called, can reasonably be trusted for a moment, or reasonably be supposed to have honest purposes in view, any longer than it depends wholly upon voluntary support.

These facts are all so vital and so self-evident, that it cannot reasonably be supposed that any one will voluntarily pay money to a “government,” for the purpose of securing its protection, unless he first make an explicit and purely voluntary contract with it for that purpose.

It is perfectly evident, therefore, that neither such voting, nor such payment of taxes, as actually takes place, proves anybody’s consent, or obligation, to support the Constitution. Consequently we have no evidence at all that the Constitution is binding upon anybody, or that anybody is under any contract or obligation whatever to support it. And nobody is under any obligation to support it. [*18]

IV.

The constitution not only binds nobody now, but it never did bind anybody. It never bound anybody, because it was never agreed to by anybody in such a manner as to make it, on general principles of law and reason, binding upon him.